The Edmund Rice Garden at Mardyke House, Cork

- Details

- Hits: 8560

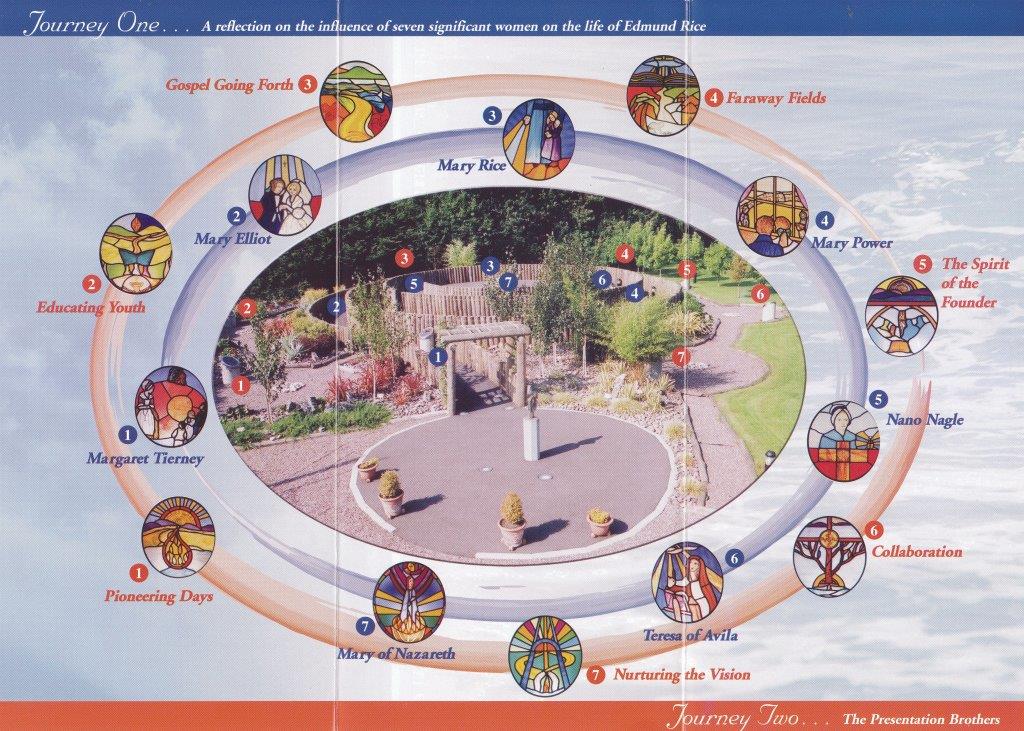

Br. Stephen O’Gorman, a Presentation Brother, conceived and built a meditation garden at Mardyke House, Cork. It sits on a beautiful piece of land that stretches down to the River Lee. The first part invites the viewer to contemplate the seven women who played a role in Edmund’s life, the second part relates the story of the Presentation Brothers.

1. Margaret Tierney

An old Callan resident remembered, “Edmund owed much to that great woman!” The big influence in the home at Westcourt was Edmund's mother, Margaret Tierney.

Margaret Tierney may well have wondered about this son of hers - Eamann, as she called him. Having fed a few poor, neighbouring children some griddle bread, she listened to Eamann. In a room off the kitchen, his first classroom, he was teaching them - in Gaelic. He was the fourth child of her second marriage. Her first husband had died leaving her with two young daughters, Joan and Jane. And she was to know widowhood again when Edmund's father Robert died in 1787; their youngest, a seventh son, was then only ten years old. But good times or bad, the gatepost of Westcourt was surely marked with the tramp's cómhortha, a sign of a generous bean on tí. Here, you would get a heat by the fire, a bite to eat, a drink, and shelter from wind and rain. In Edmund's home today, you can still see the little peep-hole near the hearth, through which his mother when baking could catch a glimpse over the half-door of a passing traveller, a spailpín or a poor beggar-woman. Her half-door was an open door; her hospitality never half-hearted.

His mother's kindly caring is not lost on Edmund. Edmund cares not only for school children, but he cares too for their parents. He cherishes the sick and comforts those in prison. The good done by Mr. Rice's religious men in Waterford reaches well beyond the walls of Mount Sion monastery to the homes, city streets, the quayside, hospitals, and to the prisons. Newspapers like The Dublin Pilot report that the "Brothers were ever to be found giving comfort to prisoners in their harsh conditions." The spirituality of giving and not counting the cost - the spirituality of St. Ignatius of Loyola and of his own mother, Margaret Tierney – becomes the spirituality of Edmund Rice.

2. Mary Rice

"That’s Edmund's girl," said the locals as Mary Rice wandered childishly through the fields at Westcourt. Edmund often took Mary to visit her grandmother in the old home at Callan.

"That’s Edmund's girl," said the locals as Mary Rice wandered childishly through the fields at Westcourt. Edmund often took Mary to visit her grandmother in the old home at Callan.

Mary Rice, Edmund's daughter, was born in heart-breaking circumstances. Her mother, Mary Elliot from a well-to-do family, was fond of hunting on horseback. In a fall, she was fatally injured; but the doctor managed to save the premature baby girl she was carrying. For Edmund, this was a shattering double blow - he had lost his wife and his little girl had been injured in the fall.

A young widower, Edmund - with the help of his step-sister Joan - now cared for and loved his growing, handicapped daughter. It was a love which lasted. Sharing with Mary the loving warmth of their home at 3 Arundel Place, Waterford, he remained by her side throughout her childhood. When he embarked on his mission, he entrusted her to his brother Patrick in Callan, later placing her in care in Carrick-on-Suir. And Mary lived until she was seventy years old. In all that time Edmund ensured that his “dear little one” was always provided for. Mary Rice died in Carrick-on-Suir in 1859. She was buried in the churchyard at nearby Carrigbeg.

The death of his wife and the care of his daughter are for Edmund maturing experiences. The remarkable tenderness that he shows to the young has its source in a compassionate love deepened by life's great joys and hard crosses. Working from his brokenness, his priorities change. Alleviation of the misery of others becomes his primary concern. In learning to love his daughter Mary, Edmund's gentle, fatherly love moulds into Christ's compassion - a compassion which saw God's image in everyone, and especially in young people however disabled, deprived, or dejected.

3. Mary Elliot

“Died at Ballybricken, the wife of Mr Rice”. So said the stark announcement in the Dublin Evening Post of January 1789. We can only guess at Edmund's anguish, desolation, and sense of loss.

“Died at Ballybricken, the wife of Mr Rice”. So said the stark announcement in the Dublin Evening Post of January 1789. We can only guess at Edmund's anguish, desolation, and sense of loss.

Little is known of Mary Elliott. Or of how and where Edmund met and fell in love with her. She enters his life as a significant figure and leaves it tragically four years later. A member of a wealthy Waterford family managing tanyards, Mary moved in the same social circle as Edmund. Romance entered their lives and they married in 1785. The marriage, of which regrettably we know so little, ended with her tragic death, leaving Edmund at twenty-seven years, a widower and father of their special daughter, Mary.

The death of his young wife was a pivotal point in his spiritual development. Into the wounded emptiness of broken heart, God's great gifts would fall. Mary Elliott was buried in the old cemetery of St Catherine’s Priory, Waterford City. Today a Courthouse and its grounds occupy the site.

Loving relationships shape us. For Edmund, a loving relationship with Mary Elliot affects him deeply; his acceptance of her untimely death refines his trusting faith. Time heals the bitter pain, but it does not dim the memories. Sorrow and suffering soften his prayerful heart. Such a tender, compassionate heart is moved with pity for others - for the poor boys he saw around the timber stacks on the city quays, for the prisoners committed to the city gaols and for the sick and dying in the city hospitals. His experience of marriage brings a richness to his later call to religious life - a different way of life, the same core ingredient - love.

4. Mary Power

“There, Edmund! There's your Melleray” His great friend, Mary Power, gestured towards the window. Edmund could see several ragged, barefoot boys round the timber stacks on the Quay. Mary Power was the wife of a wealthy corn merchant of Waterford city. Mary‘s advice was much valued by Edmund. She was a devout woman whose wise counsel Edmund often sought and it was she who helped him discern God's true call - a call to care for the poor, ragged boys in the city slums. He had just confided in her his wish to be a monk. She reminded him of what Nano Nagle was doing for poor girls in Cork city. The plight of the thousand or so boys who roamed the Waterford city streets touched him and his heart went out to them.

“There, Edmund! There's your Melleray” His great friend, Mary Power, gestured towards the window. Edmund could see several ragged, barefoot boys round the timber stacks on the Quay. Mary Power was the wife of a wealthy corn merchant of Waterford city. Mary‘s advice was much valued by Edmund. She was a devout woman whose wise counsel Edmund often sought and it was she who helped him discern God's true call - a call to care for the poor, ragged boys in the city slums. He had just confided in her his wish to be a monk. She reminded him of what Nano Nagle was doing for poor girls in Cork city. The plight of the thousand or so boys who roamed the Waterford city streets touched him and his heart went out to them.

Edmund abandoned his original intention and determined instead to devote himself unreservedly to the poor of the city. Mary Power herself cared for them. Moreover, she left money in her will for the education and clothing of poor girls attending the school run by the Presentation Sisters and for poor boys at Mount Sion Monastery school. Like Mary Power, like his own mother, he too would feed and clothe them.

And so Mount Sion became more than a school; a small bake-house was established to make daily bread for his boys, and a tailor was on hand to repair tattered clothes and make new suits.

Mary Power's words sink deeply into Edmund's heart. Once before he had felt the attraction of human love; he responded in marriage. Now, the God of love enters his life with a new call. With a worldly imprudence, against the advice of his brother Father John Rice, OSA, and with no companions as yet to help him he opens his first school in a stable in Elliott's Yard, New Street. In such a humble setting, he launches a remarkable educational project. (Not the first great venture that begins in a stable!) in the inexplicable way of the Spirit, Edmund was guided by a woman's wisdom.

5. Nano Nagle

In 1779, leaving Kilkenny to serve an apprenticeship as a merchant in Waterford City, he embarks on what will prove to be the most eventful twenty years of his life. As a successful businessman, he becomes a frequent visitor to Waterford, a city that presents a facade of commercial wealth and prosperity. What he sees, however, are so many people in need, crowded together in miserable hovels in narrow streets and dark alleyways.

In 1779, leaving Kilkenny to serve an apprenticeship as a merchant in Waterford City, he embarks on what will prove to be the most eventful twenty years of his life. As a successful businessman, he becomes a frequent visitor to Waterford, a city that presents a facade of commercial wealth and prosperity. What he sees, however, are so many people in need, crowded together in miserable hovels in narrow streets and dark alleyways.

Nano Nagle had seen similar scenes in the winding lanes of Cork in the l750’s, '60s and '70s. The more Edmund learns of the work and lifestyle of Nano Nagle, the more his own heart echoes her ideals. Like her, Edmund puts ideas of life inside a monastery wall behind him. He decides to use his time, energy and substantial fortune providing schooling for the unschooled, financial aid for those in debt, spiritual comfort for the desolate, love for the unloved. Both Nano and Edmund attract others who are inspired by them and want to share their vision.

As Nano had founded the first Irish Religious Order, the Presentation Sisters in 1775 (at a time when it was forbidden by law), Edmund in 1802 founds the first Irish Order of Brothers. Taking the Presentation Sisters Rule, he named his order the ‘Society of the Presentation‘; the aim, like that of Nano's and the Presentation Sisters, to carry forward the vision of “Gospel-love-in-the-world.”

What had begun in Nano Nagle and the Presentation Sisters in Cork inspired Edmund Rice to establish in Waterford a Society known as Presentation Brothers. In turn this society grew in number and influence and from it the Congregation of Christian Brothers was also established

Today a wonderful network is growing among the lay and religious followers of both Nano Nagle and Edmund Rice. The Nagle-Rice Family is recognized for the zeal, enthusiasm and energy of its members for God's mission of love - boundless love - to the world.

Who or what inspires you today? For what have you enthusiasm and energy? What is it that God wants most of you at this time?

6. Mary of Nazareth

Of Mary, little is said in the Gospels. Yet from his Bible reading Edmund knew and pondered her story deeply. In prayer, he deepened his understanding of this mystery: Joachim and Anne presented Mary as a young girl in the Temple where she prayed and served; as a young woman, Mary's womb becomes the temporary dwelling place of God, a Temple of the God-as-Baby. Jesus’ mission reveals that He, in his flesh is the dwelling place of God. As Jesus promised, we are the Temple where God now dwells and is active in this world. Temple-dwelling leads to Temple building.

Of Mary, little is said in the Gospels. Yet from his Bible reading Edmund knew and pondered her story deeply. In prayer, he deepened his understanding of this mystery: Joachim and Anne presented Mary as a young girl in the Temple where she prayed and served; as a young woman, Mary's womb becomes the temporary dwelling place of God, a Temple of the God-as-Baby. Jesus’ mission reveals that He, in his flesh is the dwelling place of God. As Jesus promised, we are the Temple where God now dwells and is active in this world. Temple-dwelling leads to Temple building.

Hence, Edmund and his Brothers set about a life of prayer and contemplation (Temple-dwelling) and action (Temple-building). Edmund adopted the Rule of the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and in 1808, on the feast of Mary's Assumption into heaven, a small group of eight Brothers professed the vows of religious - poverty, chastity and obedience - in the chapel of the Presentation Sisters, Waterford. Relying on the help of Mary of Nazareth, Edmund and his brothers thus began a new phase in their journey of faith. With Mary, they would present Christ again into the lives of the young and needy.

Presentation, prayer, poverty - Edmund's pithy and colloquial “a community of poor Presentation monks” conveys the essentials of his charism. Love of God, expressed in deeds; service to others rooted in prayer. Guided by the Presentation Rule, as monks they would be men of meditative prayer, living a simple life in community; as brothers of the Presentation they would serve God in others, motivated by practical compassion. The men of Mount Sion, of the North and South Mon, of India and the West Indies and of the many monasteries of Edmund's sons at home and far afield would, plainly, live a dedicated life in imitation of Our Lady of the Presentation.

7. Teresa of Avila

“That is how I treat my friends,” said Jesus. Crossing a stream on one of her journeys, Teresa had been thrown from her donkey. And Teresa replied, “And that is why you have so few friends, Lord”.

“That is how I treat my friends,” said Jesus. Crossing a stream on one of her journeys, Teresa had been thrown from her donkey. And Teresa replied, “And that is why you have so few friends, Lord”.

As a child Teresa built a little stone cell, pretending to be a hermit. This playful concern of Teresa the child became the serious concern of Teresa the woman. At twenty, she entered the Carmelites in Avila. This huge convent – there were 150 nuns - was a busy place filled with activity, too much activity for Teresa. There seemed to be little quiet focus on God. Yet she tried to lead a prayerful life. In 1554, while praying before an image of the wounded Christ, she underwent a profound conversion. She was called to reform the Carmelites. Deeply contemplative, she was still very active. She travelled the length and breadth of Spain on cranky mules and treacherous donkeys, visiting and encouraging her reformed monks and nuns.

Among Teresa's writings, The Interior Castle, avidly read by Edmund, is a disguised account of her own inward prayer journey. Teresa became Edmund's teacher, his guide on his inward journey. He kept her picture in his room and always kept her feast day with joyful heart.

“Praying,” Teresa says, “was a close sharing between friends”. Through unforeseen personal tragedy, Edmund finds such a friend in Jesus. But for Teresa, the test of growth in prayer was practical love of others. Edmund, too, realizes that love and service must go hand in hand. Prayerful and practical - this is the Teresa whom Edmund so admired: “Though we do not have our Lord with us,” Teresa says, “we have our neighbour, who, for love and loving, is as good as our Lord himself.” Like teacher, like pupil. “Were we to know,” Edmund says, “the merit of only going from one street to another, to serve a neighbour for the love of God, we should prize it more than gold or silver.”