Life of Edmund 1762 - 1810

- Details

- Hits: 100480

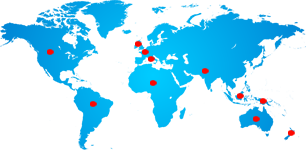

The World into which Edmund was Born

The years 1762 to 1844 were a period of tremendous importance as vast changes were taking place in the political, economic and social structures of many lands.In the year 1762 the world had a lot to occupy its attention. Foremost was the Seven Years War in which nearly all European nations were embroiled until 1763. Among the chief causes was the fight between Britain and France for supremacy on the seas, and in North America, the West Indies and India. As a result of her success, Britain would stand foremost among the European powers in the extent of her overseas colonies, which would be extended to include New Zealand, Australia, South Africa and Hong Kong. A supply of raw materials for industry as well as precious stones and metals was assured. The age of intensive missionary activity, the search for souls, was also being launched on a vast scale.

Monsieur Jean Jacques Rousseau had created quite a stir with his new book Le Contrat Social, which opened with the words “man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains”, and his new theory of the sovereignty of the people was eagerly discussed throughout France. So too was the recent decision of the Parlement of Paris to abolish the Jesuits, confiscate their property and secularize the members. The French Revolution would become the result of a long and careful attack on existing institutions by clever writers and thinkers who influenced an intelligent public. Eventually the revolutionary ideas of liberalism and nationalism spread throughout Europe by war. Karl Marx moved to Paris in 1844 and there he met Friedrich Engels. Together they produced The Communist Manifesto in 1847.

In Manchester there was talk of “muck and money”, for the new canals had cut the price of coal by 50%. The Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions were underway. Robert Peel had just invented a new carding machine that was transforming the cotton trade, Josiah Wedgewood had started to produce his famous chinaware and would soon be in mass-production allowing the wooden platters and earthenware bowls to be replaced in people’s homes. Farming methods and the time-honoured communal system of small holdings were being replaced by intensive and partly-mechanised processes on the fenced-off lands of the of the capitalist farmer. The handiwork of the cottages was being overtaken by power-driven machines in urban factories, and people left the countryside in search of jobs there. The demand was such that women and children were employed in the factory and the mine. While the conditions were deadly – long hours for low pay, costly food, filthy hovels, streets rotten with sewage, and towns disease-ridden - human life was too cheap to worry about.

In Ireland the Whiteboys and other secret societies – papists and anarchists, protesting high rents, wretched living conditions, recurring famines and high tithes paid to an alien church – were upsetting the country with their attacks on tithe collectors and animals. The Parliament was in session and had just generously voted £112,000 to educate young Catholics caught begging on the streets, to bring them up as Protestants.

People began to emigrate to the large cities of Britain, hoping to find employment in the factories. Priests and religious went with them, including the Brothers who went to Preston in 1825.

What was perceived as toleration in not enforcing some of the Penal Laws was considered by others as a sign of contempt – Ireland had been defeated and the whip was no longer needed. The Catholic Relief Act of 1792 conceded permission for a Catholic to open a school without first acquiring a licence from the Protestant Bishop. Since 1791 the United Irishmen, under Wolfe Tone, were open to Catholic members in an attempt to show that Catholics and Protestants could live and work in harmony. Edmund witnessed the futile rebellion of 1798 and saw how the Act of Union of 1800 failed to grant Catholic Emancipation. He saw the growth of the Catholic Association under the leadership of O’Connell, eventually leading to Emancipation in 1829.

Across the Atlantic the colonists were developing their country, striking out on their own, now that the French menace in Canada had been removed. In 1776, when Edmund was 14, the American colonies declared their independence.

Edmund Rice’s Early Life in Callan

The Rices of Munster are almost entirely of Welsh origin, where the commonest forms were Reece, Ruys and Rhys. This family had entered England with William the Conqueror in 1066. Several of these families came to Ireland and settled on the southern coast particularly in Waterford, Kerry and to a less extent in Cork. There are indications that the Waterford Rices moved north towards Kilkenny. The Red Book of Ormond, giving the extent of the Manor of Knocktopher on 23 July 1312, records the names of Philip, William, John and Matthew Rys. The Calendar of Ormond Deeds mentions that near Knocktopher there “is a townland of Riceslands called from the family of Rys or Rice.” Moreover a James Rice was a Burgher of Kilkenny in 1383 and a Gilbert Rice was a member of Kilkenny Council in 1434. It is thus clear that the name Rice was well established in Kilkenny and district from the fourteenth century.

The Rices of Munster are almost entirely of Welsh origin, where the commonest forms were Reece, Ruys and Rhys. This family had entered England with William the Conqueror in 1066. Several of these families came to Ireland and settled on the southern coast particularly in Waterford, Kerry and to a less extent in Cork. There are indications that the Waterford Rices moved north towards Kilkenny. The Red Book of Ormond, giving the extent of the Manor of Knocktopher on 23 July 1312, records the names of Philip, William, John and Matthew Rys. The Calendar of Ormond Deeds mentions that near Knocktopher there “is a townland of Riceslands called from the family of Rys or Rice.” Moreover a James Rice was a Burgher of Kilkenny in 1383 and a Gilbert Rice was a member of Kilkenny Council in 1434. It is thus clear that the name Rice was well established in Kilkenny and district from the fourteenth century.

According to Houlihan, Robert Rice, Edmund’s father, was a tenant farmer who rented about 175 acres of land from a friendly Protestant landlord, Lord Desart. In due course, as they matured, some of Robert's seven sons replaced the hired hands who helped him work the farm. Mrs. Rice, the former Margaret Tierney, was held in highest regard by the local people as being from one of Kilkenny's most loyal Catholic families. Robert and Margaret Rice owned a comfortable home, not luxurious, but far nicer than the huts or shacks of most Catholic families. The Rices’ Protestant landlord appreciated their industry and their reliability to pay the high rent for such a large property. Thus he did not interfere with the practice of their Catholic faith.

The home Edmund knew as a youngster was one that rang with the banter of his six brothers and two step-sisters. The six-roomed thatched cottage was a very happy home with plenty of good food, much of it fresh from his father’s farm and lovingly prepared by his mother and sisters. Margaret Rice, the mother, was the heart of the family, and she delighted in each of her children and later on, in her grandchildren.

![]() Their mother was the first teacher of the Rice boys. She taught them their prayers and she and her husband were excellent role models for the boys to imitate. Priests were always welcome visitors to the home but anyone who came to the door looking for a meal was brought into the kitchen and fed, so thanks to Mrs. Rice and the family hospitality, when it was time to leave, they were no longer hungry! Like many Irish families, the rosary was recited around the fireplace each evening and although the local chapel (parish church) was very simple, even crude, it was there that the Rice family worshipped and received the sacraments. The Catholic faith, loyalty to the Pope and to the church, and all the Christian values were both lived and taught in the home of Robert and Margaret Rice. It is no wonder that one of the younger boys, John, entered the Augustinian Monastery in New Ross, County Wexford and eventually became a priest or that Edmund would become the Founder of two Congregations of Religious Brothers.

Their mother was the first teacher of the Rice boys. She taught them their prayers and she and her husband were excellent role models for the boys to imitate. Priests were always welcome visitors to the home but anyone who came to the door looking for a meal was brought into the kitchen and fed, so thanks to Mrs. Rice and the family hospitality, when it was time to leave, they were no longer hungry! Like many Irish families, the rosary was recited around the fireplace each evening and although the local chapel (parish church) was very simple, even crude, it was there that the Rice family worshipped and received the sacraments. The Catholic faith, loyalty to the Pope and to the church, and all the Christian values were both lived and taught in the home of Robert and Margaret Rice. It is no wonder that one of the younger boys, John, entered the Augustinian Monastery in New Ross, County Wexford and eventually became a priest or that Edmund would become the Founder of two Congregations of Religious Brothers.

The happy thoughts of his youthful days in Westcourt were some of the pleasant memories that Edmund evoked in his grieving after his wife’s death. He was inclined to ask the question: "Why did this tragedy have to happen to me?” Being a man of great common sense and deep faith, he realized that there were many more blessings than sorrows in his life. He liked to reflect on the prayer of Job and to make it his own: “The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away. Blessed be the name of the Lord”.

In Edmund’s day there were about 2,000 people who made their home in Callan. It was a town of narrow streets and thatched houses. It had known better days as in olden times it was a walled town of some importance. The majority of the inhabitants were quite poor and their hovels were comfortless. Most of the families were underfed and the children poorly clothed. The census reveals that about 200 of its people in the time of Edmund’s youth belonged to the Church of Ireland, the established Church, but for the most part Protestant and Catholics got along fairly well with each other. This was rather unusual in Ireland at the time, but much had to do with the local Lord Desart who was quite tolerant and generous to his tenants, as compared to landlords in other parts of the country. There were two main streets in the town, one going from north to south, the other which intersected it, went from east to west. There was a town cross erected in the middle of the village. It stood on a square base, with a lantern at the top of the cross which was the only street light in the town. On market days the women gathered at this junction with their baskets of Callan lace, fruits, vegetables and other articles that were for sale.

Callan had the reputation of being a rough and tumble town. There was an old Irish saying about it that translated into English says: "Walk, Ireland, but run through Callan.” The inference here is that the Callan natives liked a good fight and were quick to start one at the least provocation. No wonder it was known around Ireland as “Callan of the trouble”.

Westcourt, the family home and farmstead of the Rice family, was a peaceful place when compared to most of the houses in the town of Callan. The family home was quite large, although with nine children, Robert and Margaret Rice needed every bit of space to accommodate all of them. It contained four bedrooms, a parlour, a kitchen and a hallway. There were other farm buildings on the property and a number of small houses for the hired men and their families.

Westcourt, the family home and farmstead of the Rice family, was a peaceful place when compared to most of the houses in the town of Callan. The family home was quite large, although with nine children, Robert and Margaret Rice needed every bit of space to accommodate all of them. It contained four bedrooms, a parlour, a kitchen and a hallway. There were other farm buildings on the property and a number of small houses for the hired men and their families.

Both of Edmund’s parents had combined their holdings of land at the time of their marriage in 1757. Their seven sons and two step-daughters would enjoy a comfortable and care-free life on this fairly large farm. At the time Catholics were inclined to keep very quiet about their wealth. Although the children did their share of chores as they advanced in age, there was also time for games and sports. Edmund's brothers and their friends were hurlers, the favourite Irish game of the period, and they often played this sport on one of the fields on their parents’ property. “Here too he [Edmund] tested himself with boys of the locality in running, jumping, weight-throwing and in other virile exercises. He was a graceful horseman, and in the saddle he enjoyed a gallop on his favourite horse." (Quoted in W.B. Cullen). Edmund liked to fish in the King's River nearby, to swim in the pond on his father’s property, to row a boat on the river or just to sit on the banks of the Kings River to dream and to relax.

Often enough there were games for the lads to enjoy as spectators - thrilling hurling matches - played on the Callan Green especially when Tipperary, Kilkenny or Waterford competed and local players were featured in a contest. The widower Edmund could also recall memories of when he was ten or eleven when he taught the Catechism “to the poorer children of his immediate vicinity,"... [as he gathered them around him in an empty shed at the farmhouse or in a corner of the yard.] Margaret Tierney provided these poor children with some welcome food, at the conclusion of the class”. (ref. Cullen)

According to Garvan, Edmund Rice was born into such a locality in Callan, County Kilkenny, on 1 June, 1762. His mother, Margaret, had two daughters, Joan and Jane Murphy, by a previous marriage but her husband died. Later she married Robert Rice and they had seven sons of whom Edmund was the fourth. They farmed a large farm of almost 200 acres called “Westcourt.” Actually the Rices, especially as Catholics, were relatively well-off. To this day the house in which Edmund was born, and lived the early part of his life, is standing and is a place of pilgrimage.

Edmund lived a happy childhood although he could not help but see the great contrast between the wealth of the rich and the utter destitution of the poor. There was plenty of food to eat in his home; he learnt many skills working on the farm, and he was able to play sports especially the game of hurling. The beautiful surrounding countryside afforded a wonderful environment in which to grow up. Margaret Rice, his mother, was ever kind and generous to the poor, and she would encourage young Edmund to invite poor boys home to play, and to learn from him something of their religion, for she instructed Edmund well. It has been said of Margaret Rice that she was a woman “of refined manners, of great strength of mind, and of unostentatious piety.” Her influence on Edmund was enormous as the unfolding story of his life will show.

According to Blake (A Man for Our Time, 2006), Edmund Rice’s youth was unexceptional for the better-off Catholics of his time. Irish was the language of the home, with sufficient English to deal with legal and financial affairs. His parents were greatly respected in the community for their generosity, fair-mindedness and humanity. The children were fortunate in having parents whose personalities balanced so well - the father’s shrewdness, sturdy common sense and practicality complemented the mother's warmth, sensitivity and compassion. Like any boy growing up in the Kilkenny countryside, Edmund fished, swam and played hurling.

Edmund's Education as a boy

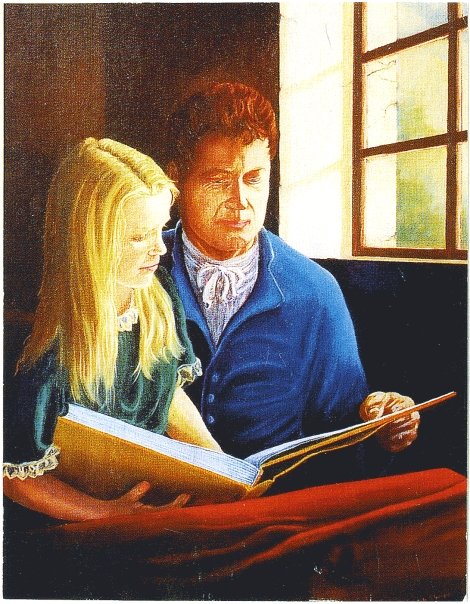

![]() According to McLoughlin, (The Price of Freedom, 2007), after initial basic education of literacy and numeracy from his mother from whom Rice “owed not a little of his later prominence” (ref. O’Toole) the Rices employed itinerant schoolmasters for their children, one of whom was Patrick Grace, known as “An Bráithrín Liath”, the Grey Brother, on account of his premature greyness. Patrick had earned a reputation as a good school master before his entry into the Augustinan order.

According to McLoughlin, (The Price of Freedom, 2007), after initial basic education of literacy and numeracy from his mother from whom Rice “owed not a little of his later prominence” (ref. O’Toole) the Rices employed itinerant schoolmasters for their children, one of whom was Patrick Grace, known as “An Bráithrín Liath”, the Grey Brother, on account of his premature greyness. Patrick had earned a reputation as a good school master before his entry into the Augustinan order.

After leaving his Westcourt 'school', Rice “received his education in Callan and subsequently in Kilkenny”. (Grace in Normoyle) At Callan, he either attended a school attached to the newly re-opened Augustinian novitiate, conducted by the same friar, Patrick Grace, or a “hedge school” in Moate Lane that fellow Callan man Br Francis Grace attended. Around the age of 15, young Edmund was sent for two years to an advanced academy at Kilkenny, sixteen kilometres north of Westcourt.

The academy that Rice Went to was probably the predecessor of the reputable Catholic school, Burrell Hall. The fee for commercial subjects was £20 per annum, a relatively large sum, which implied the quality of the school and the financial position of the Rice family. It also indicated the promise Edmund must have exhibited for this sum to be invested in him. The previous three brothers appeared not to have had such an education. (see McLoughlin pp12-16)

Patrick Grace was a native of Cappahayden, near Callan. As a young man he was a dominie or travelling schoolmaster. Aged 27 he entered the Augustinian Order. Following his novitiate in Lisbon he became ill and he returned to his native air to recuperate. He was attached to the Callan community from 1775 to 1781, the years of Edmund childhood and adolescence. Patrick Grace exercised a most benign influence for good on Edmund.

The Augustinian annalist informs us: "One home where the little grey friar had a special welcome was that of the Rice family in Westcourt. His gentle influence and fatherly advice was not lost on John, who grew up under his spell."

Once, while celebrating Mass in the Callan friary church, two adjoining thatched houses converted into one building, the roof began to fall in. Several strong men in the congregation literally held the roof up until Mass was concluded. All had vacated the building when the structure collapsed. No one was injured. Fr John Rice then (1812) set about building the new church, which is still in use today.

We read in the Callan OSA annals: "Today (July 1830) Father Patrick Grace of the Order of St Augustine was buried in the friars' monastery. He was 90 years of age which he passed in great holiness. He was a dominie, that is a schoolmaster, in his youth before he took upon himself Holy Orders as a friar."

Brother J.S. O'Flanagan, writing in the Mount Sion Annals, informs us: "Having been intended for trade, his parents, to qualify him better, resolved on sending him to the city of Kilkenny there to complete the education he had received in Callan. In his new sphere he had the good fortune to be placed under the care of a teacher no less learned than pious. This worthy man, deeply impressed with the truths of our holy religion communicated the same both by word and example to his youthful charges. In after life Mr Rice, when speaking of this good man, always did so with respect, affection and gratitude. It cannot be doubted but the early lessons of virtue had the effect of producing abundant fruit in due season."

1779 Edmund enters business with his uncle in Waterford

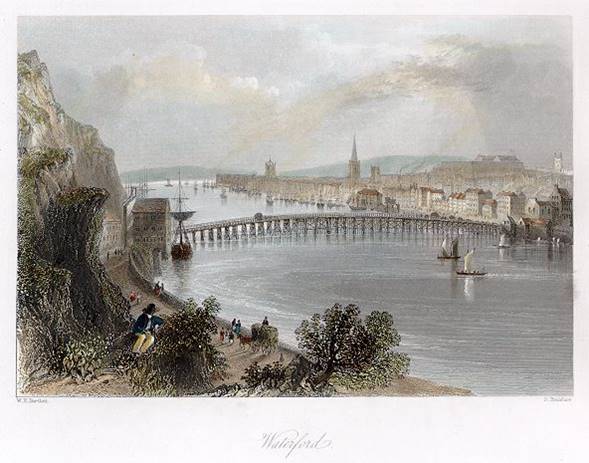

Edmund Rice arrived in Waterford in 1779. As there was no bridge across the river Suir, he would have taken the ferry from the Kilkenny side into the city.

Edmund Rice arrived in Waterford in 1779. As there was no bridge across the river Suir, he would have taken the ferry from the Kilkenny side into the city.

By the mid eighteenth century, Waterford was a city with a thriving port and centre for the processing of the tillage and dairying produce of its hinterland. It manufactured and shipped goods to Newfoundland, England and mainland Europe. By the time Edmund Rice moved to Waterford the port traded in a wide range of goods such as butter, flour, sugar, salted beef and bacon, tea, coffee, beer, whiskey, tallow, hemp, dried fish, cod oil, spices, soap, timber, pitch and tar. The Protestant Ascendancy held trade in contempt and this facilitated the upward mobility of Catholic merchants at a time when the law didn't permit them to buy land or take long leases.

The quay impressed visitors to Waterford. In 1746 it was described as: "about half a mile in length and of considerable breadth, not inferior to but rather exceeds the most celebrated in Europe. To it the largest trading vessels may conveniently come up, both to load and unload... The Exchange, Custom House and other public buildings, ranged along the quay are no small addition to its beauty" (C. Smith).

Lewis' Topographical Survey (1837) tells us a lot about Waterford ass a city of maritime trade and commerce:

Lewis' Topographical Survey (1837) tells us a lot about Waterford ass a city of maritime trade and commerce:

"On an average of three years from 1831 to 1834, the quantity of provisions exported annually was, 38 tierces of beef, 880 tierces and 1795 barrels of pork, 392,613 flitches of bacon, 13,284 cwt of butter, 19,139 cwt. of lard, 152,1I3, barrels of wheat, 160,954 barrels of oats, 27,045 barrels of barley, 403,852 cwt. of flour, 18,640 cwt. of oatmeal, and 2857 cwt of bread.

Of livestock the number annually exported, during the same period, was, on an average, 44,241 pigs, 5808 head of cattle, and 9729, sheep; the aggregate value of all which, with the provisions, amounted to £2,209,668.

The principal imports are tobacco, sugar, tea, coffee, pepper, tallow, pitch and tar, hemp, flax, wine, iron, potashes, hides, cotton, dye-stuffs, timber, staves, saltpetre, and brimstone, from foreign ports; and coal, calm, soap, iron, slate, spirits, printed calico, earthenware, hardware, crown and window glass, glass bottles, bricks, tiles, gun-powder, and bark, from the ports of Great Britain.

The gross estimated value of the imports in a recent year was £1,274,154, whereof £66,630 were for coal, slates, &C.; £27,659 iron and other metals, hardware, this improvement amounted to £21,901, towards which machinery, &c.; £665,386 woollens, cottons, silks, &c.; government contributed £14,588, and the remainder £153,667 tea, coffee, and sugar; £5750 wines; was paid from duties levied on the shipping under £102,900 tobacco; and the remainder in various other."

Edmund was to become an apprentice to his uncle Michael Rice, 'a victualler and ship chandler', ran a business in Barronstrand Street exporting goods to Bristol and supplying some of the 1,000 ships that sailed into waterford each year with everything needed for long trips at sea - including cured meats, sail-cloth, cords, ropes, oil, biscuits and salt. The French Wars, after 1793, brought a great boom in supplying beef and pork. Quickly Edmund learnt the tricks of this trade and took to the business side of things. He had an eye for detail and a wonderful way with people.

Waterford was the second largest port in all Europe at this time, but this attracted many poor people from the countryside, driven from their land, and hoping to gain some kind of livelihood even if it was from begging in the city.

Living with his uncle at Arundel Place, just off the quays, Edmund had to adjust to his new life in Waterford now that he was earning money and having a good deal or freedom. It seems he was not always exemplary, for it was reported of him on a visit back to his home in Callan, that an old poet, James Phelan of Coolagh, met young Rice after Mass in the parish church and chided him for some misconduct in the church. Edmund was told in no uncertain terms that his attitude in the House of God was unbecoming of a Catholic. To his credit Edmund took this admonition to heart, and the remarks had a very steadying effect on him. (ref. John Shelly in Memories)

Rather enigmatically Maurice Lenihan, editor of The Tipperary Vindicator, wrote of Edmund at the time of his death, and after he had very generously praised him: “We believe that Mr. Rice’s early life had not given promise of that religious earnestness which he (later) began to display”. It would certainly not be an exaggeration to say that Edmund went through some kind of “conversion” at this stage of his life.

According to Houlihan, young Edmund Rice was to become one of waterford's most successful and respected citizens. It did not take him long to set his roots down in the city that would be his home for the next 65 years. Fresh from his training at the academy in Kilkenny, Edmund was welcomed by his uncle Michael Rice who had two sons of his own and who treated his nephew as if he were a third son. Edmund threw himself into the work at his uncle’s provisioning company and Michael Rice was quite happy to have his help in managing his prosperous concern, especially since neither of his sons was interested in this type of work. Edmund’s organizing skills and his ability to work well with others resulted in expanding and making many improvements so that profits continued to mount. “Soon Edmund became a familiar figure in his uncle’s stores in Baronstrand Street, the warehouses on the quay, on board ship, or as he rode on horseback to buy cattle and farm produce to stock the ships in Waterford Harbour. He quickly won his uncle’s confidence, and a deep affection grew up between them. The business thrived.” (ref. Blake)

At Westcourt, his mother and father were proud of their son the young merchant. They knew that his uncle was very satisfied with him and that recommendation was good enough for them. In September, 1787, Mr. Robert Rice, Edmund’s father, drew up his will and to the amazement of no one in the family, he appointed Edmund executor. This made Edmund the legal head of the family. Robert Rice knew all of his sons very well and considered Edmund to be the one to take charge of things when he had passed away. The will provided for his ‘dearly beloved wife Margaret’, that she would have the home at Westcourt. There were provisions for each family member. Land records show that Edmund purchased his brothers’ shares of the land in due course. “It was a measure of the trust his father placed in Edmund, that he was made executor of the will. This was a delicate matter and demanded efficiency and integrity.” (ref. Normoyle) A few years later Edmund would also administer the last will of his youngest brother, Michael, who died in Waterford. With good reason, his parents and his siblings had confidence in their son and brother.

But there was much more to Edmund Rice than business acumen. He was a devout Catholic layman who made no secret about his love for the Church and all it stood for. His daily routine began with attendance at Mass in St. Patrick's chapel near his home, and even though it was quite uncommon among Catholics of the day, he frequently received communion. Though the Jesuis had been suppressed and finally abolished by the Holy See in 1773, Edmund was in contact with several Jesuits who he knew, and after the restoration of the Jesuits in 1811, several of his prominent spiritual mentors were members of the Order.

But there was much more to Edmund Rice than business acumen. He was a devout Catholic layman who made no secret about his love for the Church and all it stood for. His daily routine began with attendance at Mass in St. Patrick's chapel near his home, and even though it was quite uncommon among Catholics of the day, he frequently received communion. Though the Jesuis had been suppressed and finally abolished by the Holy See in 1773, Edmund was in contact with several Jesuits who he knew, and after the restoration of the Jesuits in 1811, several of his prominent spiritual mentors were members of the Order.

He belonged to a group of Catholic young men, most of them fellow-merchants, who were devoted to developing their spiritual lives and to performing good works. They met on a regular basis and committed themselves to works of charity, especially among the abjectly poor of the area. Edmund soon found himself involved with several other local agencies that provided social services to people in need. He used all of his business skills to see to it that the poor would receive whatever kind of aid they needed. He had a special interest in the homeless, in orphans, in widows, in anyone who needed assistance of any kind. He took on the role of advocate in upholding the legal rights of those who were not able to fend for themselves in a society that looked down on Catholics, especially the poor.

Although in the early 1800's Waterford city was experiencing a wave of prosperity it had never known before, it also had a slum area which was home to many of its people and where living conditions were the lowest of the low. Jobs were scarce for Catholic men. What little income that did come their way was often spent in the pubs and grog shops. A professional traveller to Waterford at this time commented: “Whiskey drinking prevails to a dreadful extent in Waterford. There are between two and three hundred licensed houses; and it certainly does seem to me that among the remedial measures necessary for the tranquillity and happiness of Ireland, an alteration in the licensing system is one of the most important.” (ref. Inglis)

At this period of his life, Edmund Rice seemed to be living two lives. By day he was in his working place pouring all of his energy into managing his uncle’s firm. After hours, he was equally occupied, this time being the agent of the homeless, the rejected, the widows, orphans, street urchins, debtors or any person who sought his help. He obtained and delivered food, bedding, fuel and medicine to the needy and tried to find lodgings for those who had no homes. He became a member of several other charitable committees in order to obtain funds from various sources to support families or individuals who had no other means at their disposal. Once he joined these committees, he usually became an officer so that he could use his influence to urge the societies to increase their efforts. At times he would challenge the banks and trusts that were not prompt in paying interest to the beneficiaries of wills — usually homes for orphans, for senior citizens or other impoverished people. He became an expert in the legal procedures needed to expedite payments to such causes.

Edmund was fast becoming one of the leading citizens of Waterford. His business associates respected him for his brilliant management, for his new ideas and for his integrity in all of his affairs. He was regarded as an exemplary Catholic layman. The bishop and priests relied on him to advise them in financial matters, especially in regard to real estate. The poor looked to him as a friend and benefactor who worked tirelessly for them and their needs. He was befriended by many of the best families in Waterford and he was able to convince some of them to join him on the several committees to which he belonged as they were always in need of donations and volunteers. One of his closest associates, Brother Austin Dunphy, tells us that “Edmund Rice was one of the very few persons who was allowed to pass unchallenged at all the military posts in Waterford, Carrick-on-Suir, Clonmel, Tipperary and Limerick.” (ref. Fitzpatrick) The obvious inference from this statement is that Edmund Rice was so well known, trusted and respected at the military posts, because of his business contacts with them supplying meat, butter, cattle, sheep, oats, hay, straw, etc. that he was most reliable and consequently one of the most trusted of civilians who had access to the military authorities.

Edmund was fast becoming one of the leading citizens of Waterford. His business associates respected him for his brilliant management, for his new ideas and for his integrity in all of his affairs. He was regarded as an exemplary Catholic layman. The bishop and priests relied on him to advise them in financial matters, especially in regard to real estate. The poor looked to him as a friend and benefactor who worked tirelessly for them and their needs. He was befriended by many of the best families in Waterford and he was able to convince some of them to join him on the several committees to which he belonged as they were always in need of donations and volunteers. One of his closest associates, Brother Austin Dunphy, tells us that “Edmund Rice was one of the very few persons who was allowed to pass unchallenged at all the military posts in Waterford, Carrick-on-Suir, Clonmel, Tipperary and Limerick.” (ref. Fitzpatrick) The obvious inference from this statement is that Edmund Rice was so well known, trusted and respected at the military posts, because of his business contacts with them supplying meat, butter, cattle, sheep, oats, hay, straw, etc. that he was most reliable and consequently one of the most trusted of civilians who had access to the military authorities.

For entertainment Edmund enjoyed Irish dancing, songs and music that were traditionally a part of the culture. It is recorded of him that on occasional Sunday afternoons, Edmund took a stroll from the city out to the suburbs to a place known as “the Yellow House Inn." He enjoyed meeting his friends there and was especially happy to hear his favourite music and to join in the choruses or to participate in one of the dances or reels. A Thomas Moore song that he liked to sing “Oh! Had We Some Bright Little Isle of Our Own” was one of the popular songs of the day. Years later as a Christian Brother “Edmund had a great fund of stories that enlivened community recreation and a droll sense of humour that brought many a laugh. Sometimes, especially on festive occasions, the brothers had a concert when Edmund would join with them in singing his favourite songs from Moore's Irish Melodies?” (ref. Normoyle)

Edmund was constantly travelling to fairs and markets on horseback, negotiating the sale of pigs and cattle from farmers to fulfil his contractual obligations for the British military. He walked through all the counties on Munster and beyond it, covering as many as possible of the four and a half thousand fairs that were held annually at the time. It is not surprising that later in 1818, during Rice’s conflict with Bishop Walsh, Rice’s clerical enemies described him as “this man sometimes was a dealer in cattle and a common butcher in the streets of Waterford."

Edmund was constantly travelling to fairs and markets on horseback, negotiating the sale of pigs and cattle from farmers to fulfil his contractual obligations for the British military. He walked through all the counties on Munster and beyond it, covering as many as possible of the four and a half thousand fairs that were held annually at the time. It is not surprising that later in 1818, during Rice’s conflict with Bishop Walsh, Rice’s clerical enemies described him as “this man sometimes was a dealer in cattle and a common butcher in the streets of Waterford."

It is accurate to conclude that the intermittent hostilities England pursued with republican France and its need to provide for garrisoned troops throughout Ireland meant prosperity for the young victualler. Indeed, there were over 20,000 soldiers in over 100 barracks in the country during this time. (see McLoughlin pp19-26)

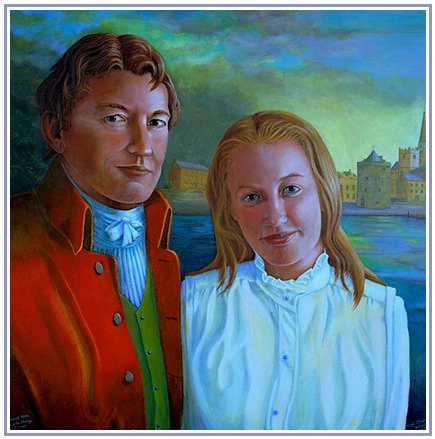

1785 Edmund marries Mary Elliot

According to Garvan, after some years in Waterford Edmund met Mary Elliott whom he came to love deeply. She came from a well-to-do family. Shortly after the death of his uncle, when he had taken over the family business, Edmund asked Mary to marry him and in 1785 they were united in matrimony. He was 23 years old. They lived in the part of Waterford called Ballybricken. All this time Edmund’s business experience was growing and he was outstandingly successful because of his intelligence, acumen, integrity, qualities of leadership, and especially his ability to get on with people. Mary shared in Edmund’s happiness, the more so because she could also rejoice in his continuing compassion for the poor. But their happiness was not without its sadness because Edmund’s father died in November 1787. Interestingly, Robert Rice made Edmund an executor of his will even though he was the fourth son.

According to Garvan, after some years in Waterford Edmund met Mary Elliott whom he came to love deeply. She came from a well-to-do family. Shortly after the death of his uncle, when he had taken over the family business, Edmund asked Mary to marry him and in 1785 they were united in matrimony. He was 23 years old. They lived in the part of Waterford called Ballybricken. All this time Edmund’s business experience was growing and he was outstandingly successful because of his intelligence, acumen, integrity, qualities of leadership, and especially his ability to get on with people. Mary shared in Edmund’s happiness, the more so because she could also rejoice in his continuing compassion for the poor. But their happiness was not without its sadness because Edmund’s father died in November 1787. Interestingly, Robert Rice made Edmund an executor of his will even though he was the fourth son.

Little is known of the girl he married and everything suggests that Edmund did not speak much about this delicate matter. Of the 250 memoirs colleced by Normoyle, only Martin O'Flynn mentions her, and he was unsure of her name. She could be "Elliot", linked with Edmund's first school in Elliot's Yard in New Street, or "Ellis", related to Patrick Ellis, one of hte first men who joined Edmund's brotherhood.

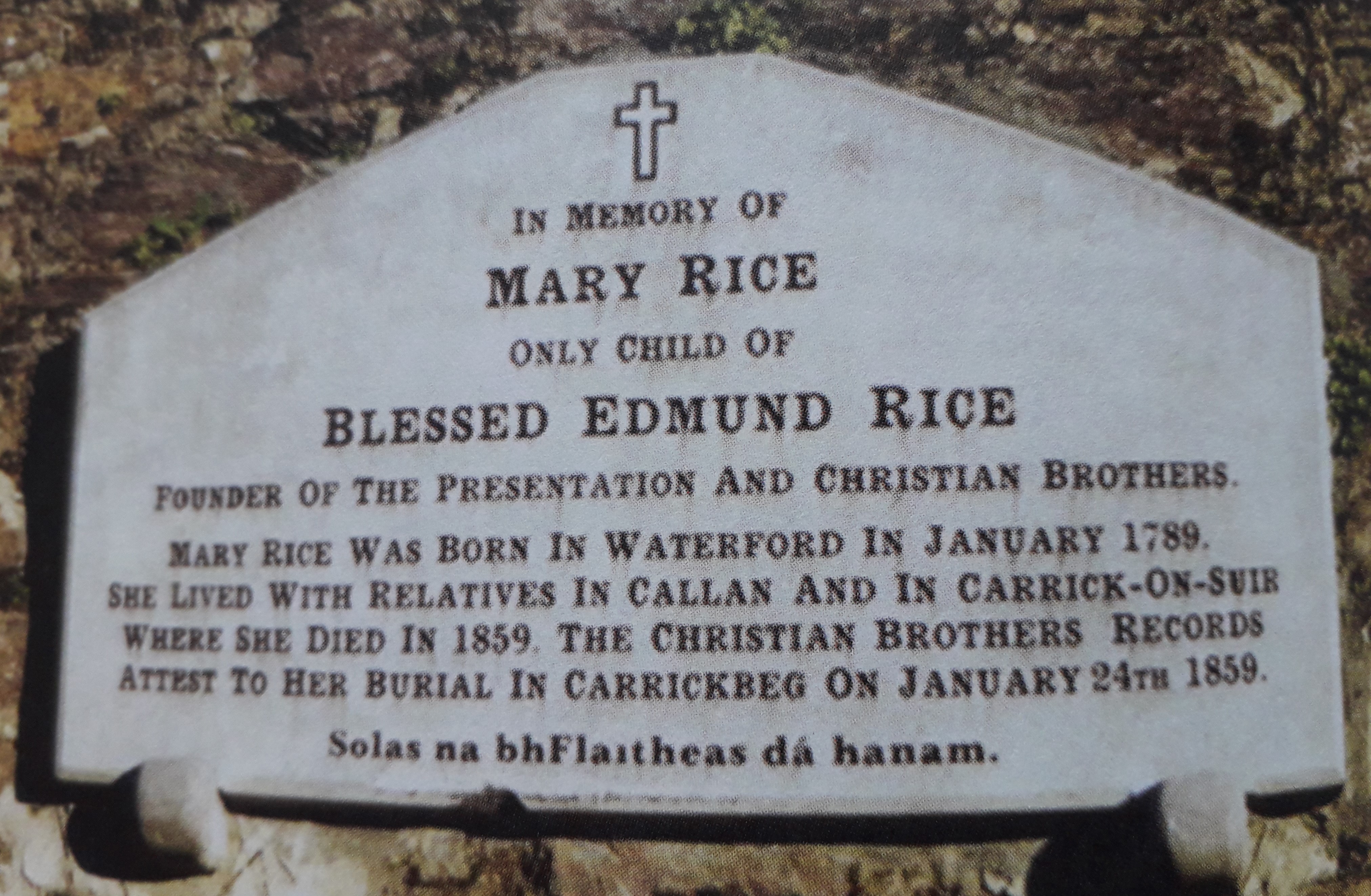

His wife was “a Miss Elliott, a young lady from a well-to-do family. Their married life was short... According to family tradition Edmund’s wife died late in her pregnancy. Their daughter, Mary, was born prematurely and never developed normally.” (ref. Positio)

1789 Tragedy strikes Edmund when his wife dies

The reference to Mrs. Rice's death appeared in newspapers for January 17, 1789 and the place of her burial is unknown. Edmund was 26 years old and the widowed father of an infant girl.

The reference to Mrs. Rice's death appeared in newspapers for January 17, 1789 and the place of her burial is unknown. Edmund was 26 years old and the widowed father of an infant girl.

A tradition grew from what Sr. Jospehine Rice recalled in 1929, that, as both she and Edmund were keen horse-riders, during her pregnancy Mary suffered some kind of fall from a horse. In January, 1789, she gave birth to a daughter but died as a result of complications. They had been married for almost four years. Edmund called his little daughter Mary after her mother, but his heart, broken over the death of his wife, was further broken because little Mary was in some way disabled.

While the exact circumstances of these happenings are still not known to us, we do know that Edmund’s grief was bitterly distressing. Years later he revealed this when, in writing about Mary Kirwan, recently widowed, he was able to identify with her, saying he knew she was in “the dregs of misery and misfortune”.

Edmund decided it was better for him to move from Ballybricken back to Arundel Place to help him forget the circumstances of his life with his wife, to place him nearer his business, and to enable his step-sister, Joan Murphy, to come to live with him to care for young Mary who was described later as "weak-headed" and "delicate".

Edmund’s love of his daughter was one of the most significant factors which brought about an entire change in the orientation of his life. He became even more sensitive to the plight of the poor whom he increasingly loved; he joined a spiritual association of men in Waterford; and he grew increasingly uneasy with the wealth he was acquiring through his business.

Edmund's experience of fatherhood - rearing his daughter Mary

The second choice would have been to send young Mary to be raised with Rice’s relatives in Westcourt. Rice’s mother was there with her eldest son Thomas. Similarly, Rice’s second older brother Patrick, whose family was childless, seems to have been particularly close to him and in the light of future events would have been willing to incorporate Mary into his family at this time. Indeed, Patrick eventually did, much later, have Mary Rice as a family member.

The last option, and the least likely for a widower without older children, was to choose to raise the child himself. This is what Edmund did. Consequently, soon after his wife’s death, Rice left his Ballybricken residence and returned to 3 Arundel Lane, adjacent to his business in Baronstrand Street, near the quay. Unable to care adequately for his baby daughter as a sole parent, Rice’s spinster half-sister Joan (Murphy) also moved into the Arundel Lane residence as housekeeper and became mother to Mary for at least the next ten years…

No doubt, the single father shared with Joan the feeding, bathing and toilet training of young Mary, guided her first tenuous steps at walking and encouraged her experimenting with talking. Did he especially treasure that day when Mary attempted to call him ‘Dada’?...

No doubt, the single father shared with Joan the feeding, bathing and toilet training of young Mary, guided her first tenuous steps at walking and encouraged her experimenting with talking. Did he especially treasure that day when Mary attempted to call him ‘Dada’?...

Since the family residence was adjacent to the business, Rice probably shared most meals with his daughter. No doubt, as a toddler, she cheekily reconnoitred and negotiated her dad’s shop and soon became the darling of many of his clients. At night. like all children, she would have loved to listen to her dads lullabies and no doubt became enraptured by his embellished storytelling, for he was fond of jokes and had a great sense of humour. Indeed. Rice was later to earn himself a reputation among his confreres as a raconteur of note, and with a fine singing voice he liked to use.

Like so many educated fathers, Rice would have introduced Mary to reading in Irish and English and basic counting and arithmetic and of course, her prayers. Would not have Edmund told her about her own precious mum, who was now with God and the Blessed Virgin and the angels, and did not both of them, before young Mary closed her eyes at night, pray to her mum to intercede for them both?

Likewise, living in the middle of the docks, Mary was exposed to an exciting and contrasting world of ships and characters from every nationality that enriched her beyond book learning. No doubt, the young dad regularly had her perched on his shoulders explaining to her the many and various dynamics and oddities characteristic of bustling, commercial Waterford…

Is it entirely coincidental that during the early 1790s, while Rice was depthing the spiritual side of his life and simultaneously engaging in other charitable initiatives, the compassionate Father, Edmund Rice, continued the tradition he had established with his young wife of inviting into the home ‘the grown and wild youths on the streets’? But this time ‘he took boys into his own house [Arundel Lane] and began to teach and instruct them’. ‘Our family tradition has it that Edmund Rice, even when in business, took a big interest in the poor boys. He met them, advised and encouraged them, and instructed them in religion and citizenship’ (John Power in Normoyle). No doubt all this was done with the wide-eyed Mary sitting on Joan’s lap watching her dad becoming ‘a father and mother to other children?

It is likely that the incomparable experience of being a loving father to his ‘little girl’ was for Rice a contributing catalyst for a brotherhood, which would likewise aspire to provide a wholesome, liberating, life-giving education. This was the type of education, he had been providing for his own “delicate daughter” who was thriving on it. Moreover, Rice himself was thriving on being a dad. (see McLoughlin pp182-186)

Providential stay one night at a Country Inn

One night, on one of his business trips, Edmund stayed at an inn and shared a room with a Friar. O'Toole suggests that this was Lawrence Callanan, the Franciscan who guided Nano Nagle and wrote her Rule in 1791.

Edmund was awakened during the night by the friar who spent practically the whole night praying. The experience made a profound impression on him. In this incident Edmund saw the finger of God and asked himself seriously whether he should live like this friar and give up his business. He had experienced how fragile can be the best joys of this World. So he resolved to give himself more to prayer and to lead a Monks life of retirement and contemplation.

The Rescue of the Slave Boy - John Thomas

During this period of Edmund’s life it was said of him that “the poor were the chief object of his attention - in fact this wonderful sympathy for Gods poor was one of his most distinctive characteristics."

Around the wharves of Waterford he saw many a sad plight among the poor. One particularly sorry sight was “Black Johnny”, a black slave boy, whom Edmund saw on a ship moored at the quay. He purchased the youth's freedom from the captain and sent him to the Presentation Sisters to be baptised and educated, subsequently providing him with a small house and the resources to set up a small business. The abolition of slavery in Britain would not occur for several more decades.

John Thomas embarked on a successful pig-rearing project, and lived in the Grace Dieu area on the outskirts of Waterford. He became a noted personality in the city and was widely known for his goodness. He left his two properties in his will to the Presentation Sisters and the Christian Brothers.

Edmund – Trustee of Various Charities

The first of many legal bequests for which Edmund became responsible was in connection with the Will of his father. Though a young man at the time of his father's death, he was the one, rather than any of his three older brothers, selected by Robert Rice to be the Executor of his Will. Soon afterwards he became involved in buying a plot of land for three Waterford women who had gone to Cork to join the Presentation Sisters, in anticipation of their return to establish a school for poor girls in 1800. Upon their return Edmund also became the Trustee of their dowries. In Thurles he became involved, with Archbishop Bray, in securing the bequest of the former Bishop, Dr. Butler, for the Presentation Sisters there.

The first of many legal bequests for which Edmund became responsible was in connection with the Will of his father. Though a young man at the time of his father's death, he was the one, rather than any of his three older brothers, selected by Robert Rice to be the Executor of his Will. Soon afterwards he became involved in buying a plot of land for three Waterford women who had gone to Cork to join the Presentation Sisters, in anticipation of their return to establish a school for poor girls in 1800. Upon their return Edmund also became the Trustee of their dowries. In Thurles he became involved, with Archbishop Bray, in securing the bequest of the former Bishop, Dr. Butler, for the Presentation Sisters there.

Thus Edmund, early in his career, acquired a reputation for integrity and skill in commercial dealings. He was, therefore, asked to become a trustee for many charities and these came to form part of his life apostolate, right up to the end of his life.

The Anne Butler Charity owned two houses which accommodated 18 poor widows after the death of Mrs. Butler in 1770. The charity also distributed food and coal. Edmund was requested to become a trustee by Bishop John Power and he took on the role in 1818, insigating legal proceedings to attempt to recover the funds of the Charity which had almost been exhausted.

The Mary Power Charity administered the legacy of £14,000 left for the benefit of the poor people of Waterford in the Will of Mary Power in 1804. When her nephew challenged the Will, and a legal judgement sided with the family, deciding that bequests to Catholic Charities was illegal, Edmund ensured that the case was placed before the Attorney General, the Commissioners of Charitable Donations and the Court of Chancery. That case was won in June 1815 and Edmund became the administrator of the Fund providing for the "Asylum" and the support of the "distressed women" who resided there.

The Captain Foran Charity was administered by Edmund to provide accommodation for ten homeless persons.

The Catherine Muldowney Trust was also administered by Edmund after the death of Miss Muldowney.

In 1794 Edmund was one of the co-founders of the Distressed Roomkeepers’ Association. Its members were aware of the frightening poverty existing in the crowded slums of Waterford. They also knew there were a lot of elderly people living alone, uncared for and forgotten. Edmund and his associates began to search the city for these people and it was at this time that the wretched conditions of neglected boys became fully apparent to him.

Possibly as a result of visiting the homes of poor families, in 1798 Edmund was instrumental, with Dean Hearn, in founding the Trinitarian Orphan Society. They established a refuge in the large Congreve mansion near New Street. The refuge would provide home and education for fifty boys and fifty girls, all orphans. Later Bishop Power left him £50 in his will for the Society, showing that he continued to be personally involved in the work.

The Waterford Mendicity Asylum was established in 1821 to alleviate the suffering of people coming to the city looking for relief from the suffering caused by famine and crop failures. It was sponsored mainly by the wealthy non-Catholic elements of the community - its Patron was the Protestant Bishop and its President was the Protestant Mayor. Edmund Rice became a member of the Management Committee. The establishment was maintained by subscriptions paid by its members, along with donations and collections, bringing in an annual income of about £1,000. Edmund, until his death, was an annual subscriber of two guineas, and records show his ongoing donations of clothing, vegetables and meat.

A large three-storey building, situated beside St. John’s bridge, was rented to be the headquarters of the non-resident “Mendicant Asylum” and it was there that street beggars gathered each morning. On the upper floor two school-rooms were fitted out, for girls and boys, under the tuition of a paid master and assistant. The middle floor had workshops for spinning wool, weaving flax and knitting where women were employed most of the day, producing woollen and linen fabrics as well as canvas, sacks and mops for the local markets. The men and boys were employed cleaning the city streets in the mornings and later were engaged in grinding oyster shells and limestone, useful for improving soil in farming districts. Local doctors attended in rotation each week. Breakfast consisted of porridge and buttermilk, dinner was mainly potatoes. Milk and bread were reserved for nursing children and the sick. The Mayor sometimes sent meat and fish confiscated at the city markets to supplement the diet.

The happy first assembly of Members in 1822 recorded that 575 beggars had been supported during the first year and Edmund Rice seconded a resolution at the meeting thanking “the clergymen of the different religious persuasions in this city for their zealous co-operation”. At the AGM in 1831 two Protestant clergymen, Lawson and Ryland, proposed a resolution “That to the gentlemen of Mr. Rice's establishment we return our most cordial thanks for their prompt attendance on all Sundays and holidays at the Mendicant Asylum, to impart religious instruction to the male part of the inmates of the institution”.

Edmund's Friendship with Tadhg Gaelach Ó Súilleabháin

Tadhg Gaelach Ó Súilleabháin (1715-1795) was a wandering poet of irregular habits but a regular visitor to Edmund’s home in Arundel Place at this time. It is said that Edmund first met Tadhg at the Yellow House Inn, a centre for music and poetry a few kilometres from Waterford, and they sometimes had a Sunday-afternoon stroll together. Through Edmund’s influence his life was transformed. Before Tadhg died on the steps of the Cathedral in 1795 he had published, with Edmund’s help, a volume of deeply expressive poems. Indeed, with Edmund practical kindness and spirituality went hand in hand. According to O'Dwyer Towards a History of Irish Spirituality (1995), Tadhg Gaelach was the most influential religious poet of the 18th century in Ireland. His contribution to the piety of the faithful in his own and succeeding generations cannot be stressed too strongly. The fact that his poems have seen at least 40 editions puts him poles apart from any other writer. He seems to have undergone a deep spiritual conversion around 1767. Most of his religious poetry was composed around Dungarvan, Co. Waterford. His poem "A Mhór-Mhic Chailce na soillse aoibhinn" is considered to be one of the best religious poems in Gaelic literature. Some of his poems were hymns sung to well-known Irish airs, such as "Duan Chroí Íosa" (available on YouTube). His hymns were a consolation, joy, source of counsel and spiritual direction for the ordinary people. It is believed that he died in the doorway of the cathedral in Waterford while saying his prayers, and a plaque has been erected there to remember him.

According to O'Dwyer Towards a History of Irish Spirituality (1995), Tadhg Gaelach was the most influential religious poet of the 18th century in Ireland. His contribution to the piety of the faithful in his own and succeeding generations cannot be stressed too strongly. The fact that his poems have seen at least 40 editions puts him poles apart from any other writer. He seems to have undergone a deep spiritual conversion around 1767. Most of his religious poetry was composed around Dungarvan, Co. Waterford. His poem "A Mhór-Mhic Chailce na soillse aoibhinn" is considered to be one of the best religious poems in Gaelic literature. Some of his poems were hymns sung to well-known Irish airs, such as "Duan Chroí Íosa" (available on YouTube). His hymns were a consolation, joy, source of counsel and spiritual direction for the ordinary people. It is believed that he died in the doorway of the cathedral in Waterford while saying his prayers, and a plaque has been erected there to remember him.

Years of spiritual growth and discernment

According to Houlihan, Edmund, being a young man without a wife and with an infant who needed extraordinary attention and care, was forced in his desolation to re-think his options for the years that lay ahead. He did not panic, nor did he lose confidence in a provident God.

According to Houlihan, Edmund, being a young man without a wife and with an infant who needed extraordinary attention and care, was forced in his desolation to re-think his options for the years that lay ahead. He did not panic, nor did he lose confidence in a provident God.

Upon his return to Arundel Place, Edmund became more closely associated with the Jesuits who ran the parish of St. Patrick’s in Jenkin's Lane nearby. Frequently he was to be found in their Church in prayer before the Blessed Sacrament. The new cathedral in the city had been opened in 1796. From his youthful days in Callan, Edmund had a great love for the Eucharist and for making visits to the Blessed Sacrament. The Waterford priests at St. Patrick's and Father John Power at St. John’s, became close friends of his. Father Nicholas Foran was another good friend. Bishop Lanigan and later on, Bishop Marum of his home diocese of Ossory and Bishop Hussey of Waterford were not only advisors of Edmund but close friends as well. From time to time he would discuss with them his desire to know what God’s will was for him and they encouraged him to continue praying and doing his works of charity. They assured him that the Lord would help him to find the answer to his questions about his future.

With the deepening of his faith, Edmund joined a small group of men (Rice, O’Brien, Carroll, St Leger, Quan) who, like himself, felt attracted to a more profound Christian commitment than that practised by the devout middle class. Later in life he would recall with gratitude the inspiration received from the support of this little group, drawn together by the common aim of spiritual growth. As well as their commitment to private prayer, spiritual reading and attendance at Mass, it was quite usual for Edmund to gather with this group of men to recite the Rosary in the evening and to organise charitable outreach to help poor people.

Edmund was careful to record all his personal expenses. In 1791 numerous purchases were made. However, £2 was spent on one item. In today's money this sum seems trivial, at that time it represented an enormous outlay. These few pounds were spent on possibly the most significant purchase Edmund ever made. He bought a Bible, a fifth edition of Dr. Troy's new bible, published the previous year, modernised by Fr. McMahon from the archaic English of Dr. Challoner's version of the Douay–Rheims bible. His name appears on the list of 1040 subscribers that paid for a special edition which was published in 1791. For the next fifty-three years of his life that Bible was read daily; quotations are used frequently in Mr Rice's writings; by Rule his Brothers read the Bible every day; the children in school were familiar with stories in both Old and New Testaments. It is not an exaggeration to state that the 1791 Bible changed Edmund's life. It is equally true that the Word of God sustained him all through life.

He drew up a list of passages from the bible that had a special application to his life as a merchant and he recorded them on the fly leaf of the sacred book. The texts he noted on the frontispiece reveal how the care of the poor, especially in bringing them some justice in their wretched state, was uppermost in his mind:

- “Give to the one Who asks of you, and do not turn your back on one who Wants to borrow.” Mt. 5: 42.

- “But rather, love your enemies and do good to them, and lend expecting nothing back; then your reward will be great and you will be children of the Most High, for he himself is kind to the ungrateful and the Wicked.” Lk. 6: 35.

- “He who oppresses the poor to enrich himself will yield up his gains to the rich as sheer loss.” Prov. Z2: 16.

- “You shall not demand interest from your countrymen on a loan of money or of food or of anything else on which interest is usually demanded.” Deut. Z3: Z0.

- “If you lend money to one of your poor neighbours among my people, you shall not act like an extortioner toward him by demanding interest from him.” Exod. 22: Z4.

- “Who lends not his money at usury and accepts no bribe against the innocent.” Ps. 15: 5.

According to Garvan, from a close study of these short passages, one can get some insights into the soul of Edmund. One of them in particular seems to point to his present situation as a Christian merchant: “Lend without any hope of return.” (Luke 6:35). This quotation also must have had some implications on his final decision to sell his thriving firm in order to give his life to the poor.

(In 1818 Edmund bought a second bible, a copy of the recently published "McNamara's Bible")

St Francis de Sales' Introduction to the Devout Life was one of the principal spiritual books that nourished Edmund's spiritual growth, both as a lay man and as a religious. The Introduction has been described as "a masterpiece of psychology, practical morality and common sense". The reader's attention is immediately focussed on Christ in the book's dedicatory prayer: 'Live Jesus. Live Jesus. Yes, Lord Jesus, live and reign in our hearts forever and ever. Amen.' Later Edmund, remembering De Sales, eagerly adopted the De La Salle aspiration to be used in communities, ‘Live Jesus in our hearts, Forever.’

In 1793 Edmund Rice bought a book which he kept and used for the rest of his life. In the 1832 Rule it is one of the five spiritual books to be kept 'in common' for the Brothers. This was The Spiritual Combat by Lorenzo Scrupoli. The fifty chapters, described as a 'course of spiritual strategy' urged people living in the world, 'to meditate, to lead better lives and, as far as possible, to extend Christ's kingdom on earth.' The book' subtitle appealed to and made the tome relevant to the Founder: 'To all those who seek piety themselves and contribute to promote it in others'. Meanwhile he was also buying other spiritual books such as The Imitation of Christ by Thomas A'Kempis.

Origin reminds us that in 1783 Edmund "formed the design of erecting an Establishment for the gratuitous education of poor boys". Keogh (2008, p. 76) suggests that "perhaps at this early stage, then, the educational initiative may simply have been just another philanthropic project which Rice aspired to add to his care for the poor, the sick and the orphans of Waterford".

The influence of Nano Nagle and the Presentation Sisters

The Presentation Sisters had been founded in Cove Lane, Cork, in 1775 by Nano Nagle to educate girls.

The Presentation Sisters had been founded in Cove Lane, Cork, in 1775 by Nano Nagle to educate girls.

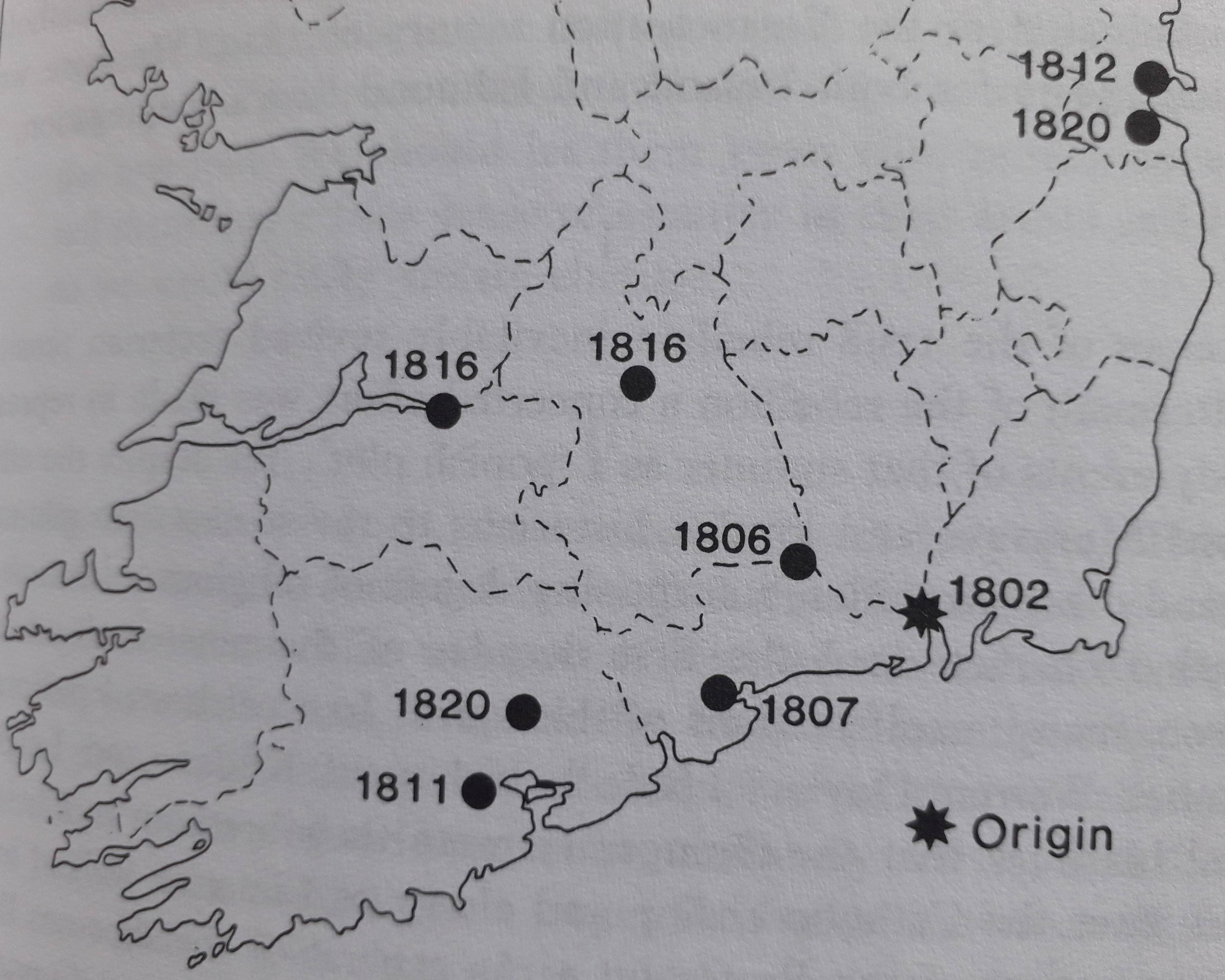

According to Austin Dunphy in Origin (the first written history of the Brothers, written in the 1820s) "About this time he (Edmund) had an opportunity of seeing the good effects of the Moral and Religious Education of the poor, in the conduct of the female children, who were instructed by the Presentation Nuns, who established themselves in this city in the year 1798. Mr. Rice now resolved on procuring a convenient site for the intended building. He decided on taking the piece of ground, which, at present, forms the Enclosure. Having the Leases perfected as may be seen by a reference to them, he commenced the building on the first day of June, 1802. About this time he was joined by two other young men, who intended to devote their lives to the gratuitous Education of poor boys".

It was said that Fr. John Power met a student of the sisters in the confessional in Waterford and was so impressed by her that he wanted to know more about the sisters who had educated her. While Nano had no sisters to send to Waterford, he arranged that three Waterford women would go to Cork to be trained and would return to Waterford to establish a convent and school. His own sister, Ellen, his widowed sister-in-law and a friend returned to Waterford in 1798.

While they were in Cork, Edmund Rice had leased a site for them to build their convent and school at Hennessy's Road. He later helped them to invest their dowries and put their enterprise on a solid footing.

Together with his own spiritual growth and his friendships with priest and bishops, this was one more influence in the shaping of Edmund's dream. When he did begin to build in 1802, he did so just across the road from the Hennessy's Road site.

A woman challenges Edmund regarding his proposed venture?

According to Garvan, the idea of joining a religious order had been maturing in Edmund, especially since his experience with the prayerful friar in the country inn. But the added desire in Edmund to found an order which would uplift poor youth through education took longer to mature. A number of traditions have been passed down to us around a significant incident of Edmund with a woman in Waterford. This encounter prompted him to move into education. One account narrates that to his step-sister, Joan Murphy, he expressed the intention of going to Europe for this purpose (of entering a monastery). She said: “It would be better for you to stay at home and devote yourself and your money to educating and instructing Irish boys”.

One account narrates that to his step-sister, Joan Murphy, he expressed the intention of going to Europe for this purpose (of entering a monastery). She said: “It would be better for you to stay at home and devote yourself and your money to educating and instructing Irish boys”.

According to The Biographical Register (1845), anonymous yet written by the hand of Br John Austin Grace, "one day as he was walking our from Waterford with his mind full of his pilgrimage to Rome, his attention was attracted to a number of poor boys who were playing on the roadside. Having questioned them on the causes of their not being in school, and having also ascertained their ignorance of the saving truths of out holy religion, and knowing, moreover, that in most instances irreligion and the vice proceeded from this ignorance, he was forcibly struck with the necessity of an institution which would afford a religious and gratuitous education to the poor of the city".

The tradition of the Brothers at Mount Sion regarding this incident is given to us by Brother Regis Hughes who wrote in 1911: “He was determined to give up everything for the love of God and become a lay-brother among the Augustinians in Rome of which Order his brother John was then a member.” To this end Edmund “made known his intention to a woman in Waterford whose advice he used to take on all important matters. She, evidently inspired by the Holy Spirit, asked him if it would not be better to do something for Waterford similar to what Nano Nagle had first done for the poor girls of the city of Cork. The suggestion sank deep into the heart of Mr. Rice”.

Hill (1920) and McCarthy (1926), following the tradition of the Presentation Sisters, attributes the advice to "Miss Power", presumed to be the sister of his friend Fr. John Power. It was said that while waiting for fr. Power at his home in Manor Street, his sister poited out a commotion in hte street outside where a group of youths were fighting and shouting. "It would be a strange and inconsistent thing for you to travel leagues of land and sea, and shut yourself up in a monastery in some distant place, while the sons of your poor countrymen at home are utterly unacquainted with the rudiments of divine or human knowledge, and running wild through the town, without a school or a teacher... Would it not be far more meritorious work, and far more exalted, to devote your life and your wealth to the instruction of these poor neglected children than to bury yourself in some Continental religious House?". Hill goes on to add "but by the way the Founder moved among the poor of Waterford, he had more opportunities of knowing the educational wants of the poor of the city than Miss Power had."

The good advice of this lady (whoever she was), uttered at a favourable opportunity, caused Edmund to make up his mind to devote himself and all he possessed to the project of educating poor youth.

According to McLoughlin, a brief diversion is warranted concerning the assertion that Joan Murphy, Rice’s half-sister, was the woman whose opinion was supposedly influential in his decision to found a teaching brotherhood… Rice himself relayed to the Waterford Presentation Nuns the influence of a “Waterford lady” on his initial decision making. In fact, an analysis of interview transcripts indicates that in addition to the Presentation Nuns’ version, there are at least eight separate sources commenting upon Rice consulting a woman or friends…

It is simplistic to think that Rice’s religious vocation was cavalierly dependent upon the urgings of the Waterford lady, as some of the above quotations imply. They suggest that he was blind to the ravages of the poor around him and it was the Waterford lady’s provocations which sensitised him to that reality. While no doubt Rice did seek counsel from the Waterford lady, it seems reasonable to conclude, that the content of this counsel would have concerned the prudence of his incipient ideas and the implications that these would have on his immediate family. Rice was noted for his exceptional reserve and privacy and it would have been contrary to his nature to share outside the family circle how the personal tragedy of his wife and his own compassion for poor children were driving him to action. Consequently, it seems probable that the Waterford lady was Joan Murphy, his step-sister, the woman with whom he shared home for near on thirty years.

Rice’s mother had given birth to seven boys in close succession and clearly the two older half-sisters held responsibilities with the mother in caring for their younger brothers. Joan Murphy had considerable experience in child-raising before she came to live in Arundel Lane as home-maker to her brother. As a result, there was a long-established intimacy between brother and sister. Living in Arundel Lane, Joan witnessed and shared in Rice’s personal traumas. At this time she probably was his closest friend. It is unlikely that the very private Rice would have gone beyond the family for intimate consultation. Likewise, he would have gone to someone whose judgement he valued and who would have been influenced by the implementation of his tentative plans. In addition to her family position and her wisdom of years and experience, it is to be remembered that she had invested £500 in Rice’s business.

For these reasons, Joan seems to be the most likely Waterford lady who would have acted as his personal confidante in his decision making. This matter is inconclusive and clearly open to debate. Nevertheless, it should be recalled that this consultation occurred sometime in 1793 or 1794, for, supposedly having gained Joan’s positive counsel, Rice sought ecclesial advice from Bishop James Lanigan in 1794.

For these reasons, Joan seems to be the most likely Waterford lady who would have acted as his personal confidante in his decision making. This matter is inconclusive and clearly open to debate. Nevertheless, it should be recalled that this consultation occurred sometime in 1793 or 1794, for, supposedly having gained Joan’s positive counsel, Rice sought ecclesial advice from Bishop James Lanigan in 1794.

According to Austin Dunphy, in the year one thousand seven hundred and ninety three, Mr. Edmund Rice of the City of Waterford formed the design of erecting an Establishment for the gratuitous Education of poor hoys. In the following year he communicated his intention on this subjects to some friends, and particularly to the Right Reverend Doctor James Lanigan, Roman Catholic Bishop of Ossory, who strongly recommended to him to carry this intention into effect; and assured him that in his opinion it proceeded from God. From this time forward Mr. Rice did not lose sight of the object he had III view; though from various causes, he did not commence the building till the year 1802.

According to James Foley (1949, Memories) "I recollect it being said that Edmund Rice was in deep doubt as to his future life after the death of his wife and that a Quaker friend of his in Waterford advised him to begin his work of charity amongst the poor of Waterford".

According to Mary Whittle (1949): Long ago great piles of timber used be stacked on the Quays, Waterford. Around these timber piles groups of wild, uncared for youths used collect. Mr. Rice became interested in the boys. He used talk to them and advise them; some of them used laugh and jeer at him. Others were interested in what he had to say. These he gradually began to teach in the evenings. After some time he collected them for instruction in New Street where he began his first school. He carried on this work for a time during the evenings while he devoted his attention to business affairs during the day. Whilst engaged in this charity there was generated in him the seed from which developed his vocation. He was very devoted to his wife and he felt her death most keenly. He was contemplating going to some religious house on the Continent when he was confirmed by the advice of a Nun to devote his energy and wealth to the education of the poor. After providing for his child he embarked on his great work.

More steps along the way

In 1796 Thomas Hussey became Bishop of Waterford after a prestigious international career. He was to be the first Bishop to reside in the city since 1652, reflecting a new confidence among Catholics. In 1797 he wrote a pastoral letter which, among other things, condemned in no uncertain terms the way poor Catholics were lured from their faith by the promise of financial and educational rewards for their children if they became Protestants.He urged the Catholic priests to "stand firm against all attempts which may be made under various pretexts to withdraw any of your flocks from the belief and practice of the Catholic religion". The reaction of the authorities was to cause the bishops expulsion from Waterford, but in Edmund it further deepened his resolve to do something significant and effective to help right the wrongs of poor Catholic boys, to offer an alternative to the endowed schools through free Catholic education. He had previously discussed similar ideas with Bishop Langan of Kilkenny.

These were years of discernment for Edmund as he tried to sift just where the Spirit was leading him. To re-marry, to carry on in his business while still helping the poor, to found an order to help overcome, through education, the injustice meted out to the poor, especially through the programmed ignorance being enforced, all of these good possibilities were tested in his prayer and in his energy for life. And over all of these was his desire to care properly for his daughter, Mary. No wonder his spiritual life deepened as prayer, sharing in the daily Eucharist, reading of the Bible and spiritual books, increased help to the poor in many ways, all intensified over this period of his life, and brought him to an ever deepening relationship with his God.

According to Keogh (2008, p. 91) "Inspired by Nano Nagle's example, and galvanised by Bishop Hussey's advocacy of Catholic education, Rice put ideas of a contemplative life behind him and embarked on a mission to do for hte neglected poor Catholic boys of Waterford what Nano Nagle had done for the girls of Cork".

He sold his buisness to his friend Thomas Quan and with the proceeds bought a 3-acre site at Ballybricken where he would build a school.

Philosophies of Education at the Time of Edmund Rice

According to McLoughlin, The Price of Freedom:The conservative social control view

Around Rice’s time, there still lingered the belief that education for the lower classes was a waste of effort and, moreover, a decidedly dangerous activity to promote. Indeed, some construed it to be an assault on the divine will and the stability of the kingdom: “The Almighty has willed that each man should be content in his station, because it is necessary that some should be above others in this world”

In France in 1763, King Louis XV’s Attorney, Louis-Rene de Caradeuc, criticised the education provided by the Jesuits and particularly the De La Salle Brothers because they encouraged middle class pretensions among the lower classes:

“They teach reading and writing to people who should never have learned more than a little drawing or how to handle tools. The good of society requires that the lower classes’ knowledge should go no further than their occupations. No man who can see beyond his depressing trade will ply it with patience and courage.”

Consequently, this educational philosophy suppressed within the poor any aspiration towards upward social mobility, convincing them to be content with their station in life. Failing to honour such a clearly evident, God-given axiom was often thought by the proponents of this conservative philosophy to be the ultimate reasons for the horrors of the French Revolution and certainly in their view was the mid-wife for the tyrant Napoleon Bonaparte…

Consequently, it is not surprising that the view that educating the poor was a futile endeavour was hurled at Edmund Rice by a friend and colleague, at the very beginning of his education endeavour. One prominent Protestant who resided in the then No.1 New Street, a Mr. Compton, a friend and admirer of Mr. Rice, thought he would reason with him on What he considered a most foolish project. He told Mr. Rice that he was but wasting his time on such a hopeless task and that he could see no chance of success for him besides a man of his business ability should not be squandering his energies on such work; that if the boys carried out the behests of their clergy in religious matters what more did they want? Why education for such

as these? This was no callous question from Mr Compton, for, from a late eighteenth century perspective, poor children were scarcely recognised as human beings. They had few rights and legally were seen primarily as their parents’ chattels, which they could use (or abuse) at

whim.

Moreover, even innovators thought of education of the lower classes as a distinct attack on social progress. Isanibard Brunel, the civil engineer responsible for the construction of much of the nineteenth century British railway system, offered the following view on the education of the poor.

“I am not one to sneer at education, but I would not give 6d. in hiring an engineman because of his knowing how to read or write. I believe that of the two, the non-reading man is best. If you are going five or six miles without anything to attract your attention, depend upon it you will begin thinking of something else. It is impossible that a man who indulges in reading should make a good engine driver; it requires a species of machine, an intelligent man, a sober man, but I would much rather not have a thinking man.”

The Liberal social control view

While the conservative social control philosophy was shared by a minority of educated persons, the liberal social control view was far more popular among politicians, clergy and the educated classes. Such a philosophy advocated education for the lower classes in order to make them satisfied and contented with their lowly position in society, thereby generating national stability…