The French School of Spirituality and its influences on Edmund Rice

- Details

- Hits: 15993

This article seeks to explain the origins of the aspiration "Live, Jesus, in our hearts" and its association with the Christian Brothers.

Introduction

The Catholic Reformation in Europe brought with it a renewal of the devotional life of the Catholic faithful in the late sixteenth century. The church was in disarray at that time and most of the clergy lacked even minimal spiritual and intellectual formation. Monasticism was rife with mediocrity and often the bishop’s office was a privilege of the nobility disposed of for personal gain. While the Council of Trent (1563) had attempted reform, its decrees were widely ignored. A significant impetus for change came from charismatic religious leaders who began reform movements in southern Europe.

Beginning with the Spanish mystics and the Society of Jesus, there was a strong desire for a personal experience of the person of Jesus and a quest for personal holiness. One of the results of this renewal was the founding of a school of spirituality which today historians would call the Bérullian current. Under Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle, Spanish mysticism was brought into the domain of French religious consciousness. Out of this Bérullian influence, one finds arising in France the work of holy people such as Jean-Jacques Olier, Jean Eudes, Vincent de Paul, Francis de Sales and Jean-Baptiste de la Salle. Their spiritual writings and witness spread beyond France, indeed reached Ireland and influenced Catholic leaders such as Edmund Rice.

Since Vatican II, religious communities have attempted to discern and articulate more clearly the charism of their respective founders as they attempt to revitalise and make relevant their role in the mission of the Church in a post-modern world. Fundamental to understanding a founder’s charism is to be able to articulate the spiritualty of that heritage. Our Christian spirituality contains two elements. First, there is the sense of ‘the beyond in our midst’ or the ‘ground of our being’, drawing us to find God in all things and in all aspects of life. Second, the understanding that it is the human response to the presence of the divine through which we can understand the sacramental meaning of events, people, and things that become for us a meeting place with God. Each person has a sense of the spiritual, a realisation that somehow we transcend ourselves: perhaps it is wonder and awe in the face of power, a beauty or a mystery that is beyond us: especially in face of the ultimate mystery of existence.

Edmund Rice’s spirituality is not something that came to him in a single moment of revelation. It was nuanced through his familial upbringing in a country that had a long history of devotions, his spiritual reading, his spiritual directors, his time growing up in a rural village and then in a larger city, his experience of marriage and fatherhood, his dreams for his Society of Brothers, and through the experience of living through the tumultuous social, political and religious upheaval of his time. It was the experience of a lifetime spent in prayer and in the presence of God. In other words, his spirituality was chiselled into the core of his being by being forged in the furnace of God’s love.

1. The French School of Spirituality

The spiritual awakening of the Spanish Counter-Reformation in the 16th century, through the spirituality of Teresa of Avila (1515-82), John of the Cross (1542-91) and Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556), became a source of inspiration for the dawn of a new encounter with the divine within Christian France. They expounded a renewal of spirituality focussing on the personal interiorisation of the spiritual life, what has been called ‘a religion of the heart’, within their religious orders and beyond.

It is customary to designate as ‘the French school’ a powerful spiritual, missionary, and reform movement that animated the Church in France in the early 17th century. Most of the devout people who led it belonged to the emerging middle class. Each was a mystic, nourished on Scripture, especially the writings of St. Paul and St. John. The leaders of the French school promoted a new sense of sacramentality that viewed the sacred and profane not as separate realms but as profoundly united. They pursued a rigorous personal asceticism and a popular piety that tapped into the emotions. They were fervent promotors of confraternities and parish missions, and not only participated in them but also clarified their underlying theology. Bérulle, Vincent de Paul and others saw the preaching of missions as the continuation of the mission of Jesus himself.

The missionary renewal went hand in hand with an educational renewal and with a multitude of apostolic initiatives. Religious orders were beginning to experience a renewal in the wake of the Council of Trent, and the early seventeenth century saw an explosion of reforms and new foundations.

Pierre de Bérulle (1575-1629) was drawn to spiritual revival and, in the void that had been left by decades of war, began to formulate a new way of living the Gospel message in the French context. He had received a very good education from the Jesuits. He became well acquainted with the best spiritual authors of his time, thanks to his visits to his cousin, Madame Acarie. In 1604 he made a journey to Spain and brought back a few Carmelite nuns of the Teresian reform. Their increase in number was spectacular. In this writings, Bérulle considers at length the "states and mysteries" of Jesus, stating that "they took place in the past, but their power will never pass away." Of all the mysteries, the Incarnation was the one on which he centered his contemplation. Bérulle held various posts as a diplomat and was made a cardinal by Urban VIII, but he has gone down in the history of spirituality as an undisputed pioneer. Over the next three centuries, the Bérullian ‘current’ came to dominate the way ‘spirituality’ was articulated and practised.

Charles de Condren succeeded Bérulle as superior of the Oratory. Though he did not leave many writings and did not carry out spectacular undertakings, his spiritual influence was profound and it was said that throughout the 1630’s he was the spiritual director of all the saints in Paris.

Jean Eudes is regarded as the founder of several religious communities, nourished by the example and teaching of this missionary and spiritual master. He was the leading spirit of the liturgical celebrations in honour of the Sacred Hearts of Mary and Jesus. He published several books based on his missionary experience. "Christian living continues and fulfils the life of Jesus Christ", he wrote. "When a Christian meditates, he continues and fulfils on earth the prayer of Jesus Christ; when he works he continues and fulfils on earth the labour of Jesus Christ… so, the Son of God’s design is to accomplish and fulfil in us all his states and mysteries. His design is to complete in us the mysteries of his Incarnation, birth, and hidden life by forming himself in us”. He warned his followers that "the greatest of all practices, the greatest of all devotions, is to be detached from all practices and to surrender to the Spirit of Jesus."

Jean-Jacques Olier was educated by the Jesuits in Lyon. After he had led a lukewarm Christian life for a few years, he experienced a conversion of heart and considered becoming a priest from apostolic motives. Under the guidance of Vincent de Paul he was ordained a priest in 1633, later founding the Sulpicians. His method of prayer is entirely centred on Jesus, as aptly illustrated in what is called the ‘Sulpician method’ which comprises three successive stages: the stage of adoration - Jesus before the eyes; the stage of communion - Jesus in the heart; the stage of cooperation - Jesus in the hands.

Louis Marie de Montfort was known in his time as a wonderful preacher. De Montfort also found time to write a number of books which went on to become classic Catholic titles and influenced several popes. He delved deep into the theological foundation of devotion to the Blessed Virgin, seeking to improve the Christian way of life of ordinary people and he promoted the practice of praying the Rosary. "Jesus, our Saviour, true God and true man must be the ultimate end of all our other devotions”, he wrote, “otherwise they would be false and misleading. He is the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end of everything”.

One final comment in this historical context is the important role of women in the development of the French spiritual tradition. Although French society kept women in a subordinate position, their influence was recognized and often fostered: Madame Acarie, the cousin of Bérulle, greatly influenced him; Mother Agnes de Jesus, Marie Rousseau, and Marie de Valence inspired Olier; Marie des Vallées influenced John Eudes; Blessed Marie Louise Trichet played an important role in de Montfort’s life. Louise de Marillac is associated with Vincent de Paul, Claude de la Colombière with Mother Margaret-Mary Alacoque, and Francis de Sales with St Jane Frances de Chantal. Maybe the most authentic Bérullian woman was Mother Madeleine de Saint Joseph, the first prioress of the first reformed Carmelite convent in France.

The role of women in shaping the spirituality of this period is an important aspect of the down-to-earth, balanced, open-minded, compassionate approach of the French School in developing and maintaining the faith life both of individuals and the wider community in a rapidly changing world. Many contemplative Congregations for women, such as the Benedictines, were renewed; and others, for example, the Visitation nuns and the Carmelites of the reform of St. Teresa, began to flourish in France.

2. Spiritual Characteristics of the French School

Central to the Christian tradition is the greatness and goodness of God: both his transcendence and immanence. Through the Middle Ages and Scholasticism, the Catholic tradition was strongly theocentric in its emphases. There was a clear emphasis, up to the time of the Reformation, on the reality that it is to God that we must look and not ourselves. The Reformation and its call for a greater reliance on Scripture rekindled an awareness of God’s immanence.

a) It was at this point that the Christocentrism of the French school took hold, especially through focussing on the event of the Incarnation. For the practitioners in the French school, the revelation of the invisible God is ultimately knowable in and through the Incarnate Word who is Jesus. Historians of spirituality have underlined the fact that Bérulle’s experience and message are characterized by the sense of the grandeur, absolute perfection, and holiness of God. For Bérulle and his followers, it is in Jesus alone, the perfect worshiper of the Father, that worship in spirit and in truth is fulfilled. Olier writes: "Our Lord Jesus Christ came into the world to bring reverence and love for his Father and to establish his kingdom and his religion. He bore witness to the respect and love for his Father that are the constituents of religion… We must consider God first rather than ourselves and act out of reverence for God rather than seek ourselves."

They understood and presented Christian living as a specific, personal, and ecclesial relationship with the person of the risen Christ. This essentially implies a relationship of deep identification with Jesus Christ. Jesus comes and lives in us through faith, love, and our apostolic commitment. This "life of Jesus in us" begins at Baptism, and it is nourished and grows by our participation in the Eucharist and in meditation. Jesus sends us, as he was sent by the Father and as he sent his Apostles after they had been enriched with the gift of the Spirit. "Christian living is the continuation and fulfilment of the life of Jesus… When a Christian meditates, he continues and fulfils the prayer of Jesus" wrote Jean Eudes. This is the application of Paul’s words: "It is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me" (Gal 2:20). This identification takes place when we are in communion with the states, dispositions, and even the sentiments of Jesus.

b) The French School is also Trinitarian, with a great devotion to the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of the risen Christ; and an awareness of the necessity for each Christian to surrender to the Spirit’s action. The divine ‘unity of essence’ is revealed to be a ‘unity of love’. In the Incarnation, “God who is unity leads everyone to unity, and through distinct degrees of unity comes and descends toward man that he might ascend toward God. God, creating and forming all things, refers them and relates them all to himself... a movement more intimate to the creature than his own being itself” writes Bérulle. It would appear that the more people meditated upon the mystery of the Incarnation, the more it moved them to the experience of the presence of God as love, real and active. This was the origin of the ‘mystical’ element of the French school.

The French School proposes that we are involved, not in a flight to the Transcendent One, but in an ecclesial movement to the interpersonal life of the Trinity through the mediation of Jesus Christ. As already implied, if the Bérullian current can accent our nothingness and sinfulness, it can also celebrate our grandeur. For as we have seen, humanity is ultimately tending toward God and thus in our very being we reflect the Trinity. There is a profound mystical sense of the Church as the Body of Christ continuing and accomplishing the life of Jesus, his prayer and mission.

The denial of the body was a means to engage in the rescuing of one’s soul from the sinfulness of the body. Thus the theme of ‘adherence to Christ’ in this tradition takes on great importance. A Christian adheres to Christ by seeking consciously to conform his or her whole life to the interior life of Jesus.

c) Another clear aspect of the spirituality and theology of the French school is a concern for the spiritual and theological renewal of individuals, and with it the renewal of the clergy. There is clearly an accent on the individual’s own personal and intimate growth in interiority. The training of priests was the constant preoccupation. The education of youth in secondary schools as well as the education of poor children in "charity schools" developed tremendously.

d) The French School showed an extremely strong apostolic and missionary commitment. Francis de Sales, then Bérulle, Condren, and many others, worked hard to bring Protestants back to the Catholic Church. The "home missions" developed considerably and were very successful. Vincent de Paul called his community the Congregation of the Mission. Many priests of the Oratory and others gave missions throughout France. Great efforts were made to renew the liturgy and the teaching of catechism and to promote charitable activities in parishes. Care of the poor and the reform of prostitutes were the constant concern of such great reformers as Vincent de Paul and Jean Eudes.

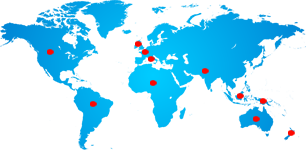

The foreign missions fired many priests and lay people with enthusiasm. Canada attracted the Jesuits, as well as Recollects, Sulpicians, Ursulines and Augustinians; the Capuchins and others left for the Middle East; and the work of Jesuits like Alexandre de Rhodes in Vietnam was to bear lasting fruit. The seminary for the foreign missions opened in Paris in 1663.

In his Mémoires, Olier wrote: "During my meditation I have been granted the grace to understand that Our Lord has come to reside in the Blessed Sacrament of the altar in order to continue his mission until the end of the world and to reveal the glory of his Father. I also realized that all apostolic persons and the apostles are Christ-bearers: they take Our Lord with them wherever they go; they are, as it were, sacraments bearing Christ in order that under their appearance and through them he may proclaim the glory of his Father."

3. The Spirituality of Francis de Sales

During this same period, Francis de Sales (1567-1622) was born in the Duchy of Savoy, now part of Haute-Savoie, France. He was to become a vital figure in this ‘spiritual awakening’. From 1580’s he studied at the college of Clermont, Paris, under the care of the Jesuits and he met Bérulle a number of times in Paris. In 1588 he studied law at Padua, where the Jesuit Father Possevin was his spiritual director. His father had selected one of the noblest heiresses of Savoy to be the partner of his future life, but Francis declared his intention of embracing the ecclesiastical life. He was consecrated Bishop of Geneva 1602.

It was said of him that he led the entire century into the world of devotion and the love of God. Seeking to teach a way of holiness that was attractive and accessible to the common people in “the soldiers’ camp, the craftsman’s workshop, the court of princes and the homes of married people”, his first step was to institute catechetical instructions for the faithful, both young and old. He made prudent regulations for the guidance of his clergy. He carefully visited the parishes scattered through the rugged mountains of his diocese. He reformed the religious communities. His goodness, patience and mildness became proverbial as he preached surrender unto the gentleness of God. He had an intense love for the poor. In 1610, together with Jane Frances de Chantal, he founded the Institute of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin, for young girls and widows called to the religious life. Their intention was that the women would not be bound to the rules of cloister and other austerities, but instead would be able to dedicate themselves to works of charity.

Francis of Sales is decidedly optimistic in his theology. He is most impressed with the abundance of the means of salvation. Two of his books, Introduction to the Devout Life and Treatise on the Love of God, became classics in French spirituality and have had a strong influence on the development of a search for personal holiness.

An initial consideration of his spirituality with that of the Bérullian school shows that they held much in common, particularly the preference for a Christocentric over a theocentric focus: an immanent Christ to the transcendent Creator. Yet there are some ‘subtle’ differences that can be identified in their spiritual outlooks.

Traditionally contemplatives follow a passive way of discipleship. This search for God is lived in solitude or through religious communities and usually involves a separation from ordinary society. Apostolic spirituality is, by contrast, an active way of discipleship. At the heart is the assurance that one has been sent into the world to announce, both in word and deed, the saving power of God. The French school had been somewhat contemplative in its outlook. It was Francis de Sales who in his seminal work, Introduction to the Devout Life, re-established the primordial belief of the apostolic church, the universal call to holiness:

“Almost all those who have written concerning the devout life have had chiefly in view persons who have altogether quitted the world; but my object is to teach those who are living in towns, at court, in their own households and whose calling obliges them to a social life who are apt to reject all attempts to lead a devout life under the plea of impossibility … [these] can find a wellspring of piety amid the bitter waves of society and hover amid the flames of earthly lusts without singeing the wings of the devout life”.

A second issue might be described in terms of a shift from an apophatic to a kataphatic spirituality. Apophatic spirituality affirms the absolute unknowability of God and rejects all conceptual attempts to name, symbolise, or speak about God in concrete images. Kataphatic spirituality affirms that God the creator can be known by way of analogy, through images, symbols, and concepts drawn from human experience in the created world. Bérulle and the French school were more apophatic in their outlook. Over time, this strand led to the development in France of a strongly ascetical spirituality. An overemphasis of this approach led to Quietism, which was an extreme form of spiritual passivity that surrenders all human faculties to the divine, and Jansenism which brought with it a strong moral rigorism recognising that in one’s nothingness and sinfulness in the presence of God, one can only be relieved through seeking maximal purity of moral effort.

Francis de Sales was more kataphatic in his outlook. His is a spirituality of love more rooted in the visible world. It is a practical, down-to-earth spirituality to be found in the living out of the ordinariness of the everyday. Here a heart ablaze with the love of God is essential, a love fuelled by prayer and the participation in the sacramental life of the Church. Every form of communication – preaching, teaching, writing, spiritual guidance, daily exchanges – is potentially a medium through which heart might speak to heart, and the love of God be kindled. We find here again the Pauline longing of the heart “The fruits of the spirit are love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, trustfulness, gentleness and self-control; no law can touch such things as these.” (Gal 5:22).

In the Bérullian current there was a pessimism about human nature. They believed that a spirit of abnegation would lead one to have a very low estimate of all created things, and especially of oneself. The position of Francis de Sales contrasts with this pessimism and there is a strong spirit of optimism in his entire outlook. He was well aware of human weakness and frailty, but his emphasis was much more on our restoration in Christ. The love of God was the foundation of his own life, and he sought to bring that love of God to life in the hearts of the people he encountered from all walks of life. As de Sales states:

“Although our human nature… is now gravely wounded by sin, nevertheless the holy tendency is still ours to love God above all things as well as the natural light which shows us that His sovereign goodness is more lovable than anything else. Nor is it possible that a man thinking attentively about God, will not fail to experience a certain ‘élan’ of love that arouses in the depth of our heart.”

Central to the optimistic spirituality of de Sales is the belief that human beings are created by and for the God of love and endowed with a desire to return in love to God. This God-directedness is discovered in the heart – the dynamic, holistic core of the person. De Sales in his Introduction to the Devout Life, sought to extend the pursuit of perfection far beyond the monastic context or to the intellectual and educated elite. True devotion is simply the true love of God that ‘not only leads us to do well but also to do this carefully, frequently, and promptly.’ This life of devotion is possible for any person but ‘the gentleman, the worker, the servant, the prince, the widow, the young girl, and the married woman exercise it in different ways… It must also be adapted to the strength, responsibilities and duties of each person.’

The hallmark of a saint is one who can appropriate those elements of the rich tapestry of the spiritual life of the Church down through the centuries and make it uniquely their own. Their awareness of God’s love enables them to live authentically their unique vocation and in response move out in mission to further the kingdom of God among people of all nations. Francis de Sales showed an originality and depth in his spiritual writings.

a) Incarnation: The Presence of God

This theme, which runs through the whole of Christian spirituality, became particularly important from the 17th century onwards. Presence is inconceivable without relationship. Human consciousness can only conceptualise and describe the experience of God by analogy. Thought alone will not allow us to encounter God, we know God only through love. “Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God; and everyone who loves is born of God and knows God.” (1 John 4:7).

Francis in his Introduction to the Devout Life outlines that the basis of the relationship is in true devotion. He states: “It is most important that you should thoroughly understand wherein lies the grace of true devotion; and that because while there is undoubtedly such a true devotion, there are also many spurious and idle semblances thereof; and unless you know what is real, you may mistake, and waste your energy in pursuing an empty, profitless shadow.”

Furthermore, he states “God has not made perfection consist in the multiplicity of acts that we do to please him but in the way we do them, which is nothing more than to do the little things we are capable of doing by vocation, doing it in love, through love and for love.” He recalls that it is in God that “we live and move and have our being” (Acts: 17:28).

He writes in his Introduction: ‘First, one must have a realisation that His Presence is universal; that is to say, that He is everywhere, and in all, and that there is no place, nothing in this world, devoid of His Most Holy Presence, so that, even as the birds on the wing meet the air continually, we meet with that Presence always and everywhere. It is a truth which all are ready to grant, but all are not equally alive to its importance and so readily lapse into carelessness and irreverence.”

For de Sales, the devout life embraces every aspect of life; the devout life finds the ideal in the ordinary. For him, there are four virtues that are common to everyone, no matter what his or her state in life, namely gentleness, temperance, modesty and humility. They are not to be seen as anything less than the foundation of the love of God put into action.

The call to live in the presence of God requires neither more nor less than a sense that one is loved totally by God. It is not just a mental belief, but one that consumes the heart and the soul. God invites and gives us the inner power necessary to live out the demands required.

b) Love of the Eucharist

Francis , outlines that the beginning of the journey to love must be a recognition of our sinfulness – those actions that ultimately lead to a breakdown in our relationship with God. He strongly urges that one must take on a spiritual director and, in Part 2 of the Introduction, talks about the necessity of prayer and devotions such as the rosary, the Divine Office or adoration of the Blessed Sacrament as a means to allow the soul to encounter God’s unrequited love. For him the ultimate source was the Sacrament of the Eucharist, “the Sun of all spiritual exercises, the very centre point of our Christian religion, the heart of all devotion, the soul of piety, that ineffable mystery which embraces the whole depth of Divine Love.”

“If any imperative hindrance prevents your presence at this Sovereign Sacrifice of Christ’s most true Presence… choose some morning hour in which to unite your intention to that of the whole Christian world, and make the same interior acts of devotion wherever you are that you would make if you were really present at the celebration of the Holy Eucharist in Church”.

c) The Centrality of Prayer both Individual and Communal

Overarching this participation in the sacramental life of the Church was his commitment to prayer, which “opens the understanding to the brightness of Divine light and the will to the warmth of heavenly love – nothing can so effectively purify the mind from its many ignorances, or the will from its perverse affections… Believe me there is no way to God save through this door.”

Prayer is both personal and communal and in this context one connects with the wider Church. It also connects with Jesus’ proclamation: “For where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them” (Mt 18:20). De Sales confidently writes: “Be ready to take part in activities of the Church… this will be pleasing to God… it is always a work of love to join with others and take part in their good works. And although it may be possible that you can use equally profitable devotions by yourself as in common with others – perhaps even you may like doing so best – nevertheless God is more glorified when we unite with our brethren and neighbours and join our offerings to theirs”.

For Francis de Sales the love of God was the foundation of his life and he sought to bring that love of God to life in the hearts of people he encountered, from all walks of life. There was a strong spirit of optimism; yet he was well aware of human weakness and frailty. He sought to lead ordinary Christians to a full and fervent interior life that would manifest itself in all aspects of their lives, which would lead to an encounter with a God, real and present, in their daily lives through experience of family, sacrament and community. It was a message for all people, religious and lay.

His focus was on an apostolic spiritualty formed by contemplative practice. His Christocentric approach to spirituality, that had at its centre a contemplation of the Incarnate Christ by a continual presence to ‘the Crib, the Cross and the Altar’, enabled him to temper the more ascetical devotional outlook of the Bérullian current. He places emphasis on a strong unity between the human and the spiritual, action and contemplation, and the interior and exterior life. Finally, in Francis De Sales there is optimism about the human person, believing that through a love of prayer and the Sacraments one can encounter the presence of God. Living in the presence of God one learns to love, and be loved, unconditionally by God.

4. Jean-Baptiste de la Salle – “Live, Jesus in our Hearts”

Jean-Baptiste de La Salle (1651-1719) had occasion at an early age to know several devout priests reputed for their knowledge and wisdom. His parents could afford to have John Baptist attend excellent schools and in 1670 he was admitted to the Sorbonne in Paris. Here he met with the disciples of Olier at the seminary of Saint Sulpice and for a year and a half had the benefit of Sulpician formation.

In his meditations, de la Salle presents God as infinitely superior to all created things: To whom ought we to give ourselves if not to the One from whom we have received everything, who alone is our Lord and our Father, and who, as Saint Paul says, has given being to all things and has made us only for himself?”

The personal experience of the Brother in his call and mission is an experience of faith. De la Salle stresses this and makes the spirit of faith one of the vital signs of the young Society: The spirit of this Institute is, first, a spirit of faith, which ought to induce those who compose it not to look upon anything but with the eyes of faith, not to do anything but in view of God, and to attribute everything to God.

Elsewhere he adds: Your faith must be a light that guides you in all things and a shining beacon to lead to heaven those you instruct. Do you have such faith that you are able to touch the hearts of your students and to inspire them with the Christian spirit? This is the greatest miracle you can perform and the one that God asks of you, for this is the purpose of your work.

Sharing in the mystery of Christ and uniting with him are at the heart of his meditations for his disciples: Attach yourselves only to Jesus Christ, his doctrine, and his holy maxims, because he has done you the honour of choosing you in preference to a great number of others to announce these truths to children, whom he loves so specially.

To know God and his Son, Jesus Christ, is for de la Salle the foundation of the Christian life. This knowledge is possible only by the light of faith. He describes the effect that faith has as the result of a personal experience with Jesus Christ: Jesus Christ, entering a soul, raises it so far above all human sentiments, through the faith that enlivens it, that it sees nothing except by the light of faith. No matter what anyone does to such a soul, nothing can disturb its constancy, make it abandon God’s service, or even diminish in the least degree the ardour it feels for God, because the darkness that previously blinded its spirit is changed into an admirable light. As a result, the soul no longer sees anything except by the eyes of faith. Do you feel that you have this disposition? Pray to the risen Christ to give it to you.

He gives a central role to the Holy Spirit, the soul of the entire life of the Brother: You need the fullness of the Spirit of God in your state, for you ought to live and be guided entirely by the spirit and the light of faith; only the Spirit of God can give you this disposition.

He focused on doing the will of God, and he searched for this will in the events of his life as well as in the whole context of his human existence. He was a man of God, imbued with faith and zeal for God’s glory, trained and guided by a solid theological foundation. He designed for himself and then for his disciples a spiritual doctrine adapted to their role as Christian educators in the service of the poor, encouraging them by his example even more than by his words. While the French School developed its spirituality largely for the clergy, De La Salle’s spirituality was addressed specifically to a group of men who were not clerics.

He calls the Brothers to realize that the good news of salvation, which gave them joy and transformed their life, must be passed on to the poor and abandoned youths entrusted to their care. When he speaks of the choice God has made of each Brother, he always joins to this choice the purpose that God has in mind: It is God who has called you, who has destined you for this work, and who has sent you to work in his vineyard. Do this, then, with all the affection of your heart, working entirely for him. One of the most striking elements in de la Salle's Meditations is the boldness with which he links the vocation of the Brother to the ministry of the Apostles. They are to be "successors of the Apostles in your task of instructing the poor and teaching them catechism". God has "given you the grace to share in the ministry of the holy Apostles”. considering mission work from a theological point of view: it was the mission of the apostles themselves, and it had to be carried out in an apostolic spirit.”

In summary then: because it is your duty to teach your disciples every day to know God, to explain to them the truths of the Gospel, and to train them in their practice, you must be entirely filled with God and burning with love for his holy law, so that your words may have their proper effect on your disciples. Preach by your example, and practice before their eyes what you wish to convince them to believe and to do.

The aspiration “Live, Jesus, in our Hearts Forever” dates back to the establishment of his Institute. It began as a signal used only by the Brothers in community, but over time was extended for use with their pupils. Where did de la Salle find his inspiration for it? We know that it was customary for the Bérullians to punctuate their day with prayers and examinations of conscience. The texts of these were nearly always centred on Jesus.

Francis de Sales had written in his Introduction, “Live, Jesus! Live, Jesus! Yes, Lord Jesus, live and reign in our hearts forever and ever. Amen”. We find a parallel in Abbe Condren's prayer: “Come, Lord Jesus, and live in your servant” and in Jean-Jacques Olier: "O Jesus, living in Mary, come and live in your servants”. Olier also heads a letter to Mme. Rousseau with the words: "Live Jesus in our hearts". De Montfort's motto during his missions was: "Long live Jesus, long live his Cross" Thus it can really be said that it was inherited partly from Saint-Sulpice Seminary and the French school. It became a living summary of a whole range of teachings on mental prayer which the Founder left his Brothers.

De la Salle was very much influenced by the spirituality of his time – we identify with Jesus living within us, not only by imitating his way of life but, more deeply, by making one’s own the mentality, the ‘heart’ of Jesus. To the Brothers who had been formed on the maxims, virtues and sentiments of Jesus Christ, de la Salle says the following: “Ask therefore the Lord of all hearts to make yours one with those of your Brothers, in that of Jesus”.

“For this reason I kneel before the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth is named, that he may grant you in accord with the riches of his glory to be strengthened with power through his Spirit in the inner self, and that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith; that you, rooted and grounded in love, may have strength to comprehend with all the holy ones what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge, so that you may be filled with all the fullness of God”. Ephesians 3: 14-19

5. The Spirituality of Edmund Rice and the Early Brothers

Some of the elements referred to above can be seen in the earliest Rule of the Presentation Brothers, that of 1802. Edmund adaptated the Rule of the Presentation Sisters, commissioned by Bishop Moylan of Cork and written by Fr. Laurence Callanan, OFM, to regulate the humble and ascetic lifestyle of his Brothers. It had a distinctly European character, with its echoes of St. Jean-Baptiste de la Salle, who had systematised the pedagogy and methods of the Catholic Reformation in his “Conduct of Christian Schools” which the Brothers had translated now into English (and which was to education what the “Spiritual Exercises” were to spirituality in that period), and of St. Francis de Sales and his focus on diligence in prayer, self-improvement and good works.

The 1802 Rule reflected Nano Nagle’s enthusiasm for the reformed devotions: the Passion, the Eucharist, and the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary. Edmund accentuated that culture, adding Saints John the Baptist, Teresa of Avila and Ignatius of Loyola to the litany of saints to whom the Rule urged particular devotion.

Edmund had a special affection for St. Teresa of Avila, whose writings inspired him through his life. He kept a picture of the Spanish mystic in his room and had a remarkable devotion to her as his life drew to a close.

A religious Rule is the written expression of what a founder sees in essence as his or her experience of charism in their own life, being deeply touched by the Spirit and being transformed from within. The 1832 Rule lays out what might be called the Edmundian way to God. Chapter 2 of his 1832 Rule constitutes an integrated theology of Edmund’s vision of a way of life inspired by a central spirit of faith, characterised by a Christ-centred detachment, and expressed in interior devotion and apostolic zeal. There is an awareness of God alone as the one who takes the initiative and is the source of all graces. The spirituality it outlines directed the Brothers towards the assimilation of the fullness of the doctrine of the Incarnation, a spirituality grounded in the Gospel. It indicates a life marked by detachment or “holy disengagement”, a life lived with purity of intention, lived “only for Christ” . The Rule called for a radical following of Christ without reserve, a total identification with Christ, a rejection of worldly ideals inspired by the primacy of spiritual values such as charity, humility and an “ardent zeal for the dear little ones” whom Christ loves.

The best synthesis and expression of this spirit was made a keynote of the life of the Society by the authors of the Rule, through the use of the aspiration “Live, Jesus, in our hearts forever” stemming from the great Pauline prayer found in Ephesians 3:15-19. The sentiment was to be found in the Gaelic tradition and was prominent in the French school of spirituality. The 1832 Rule envisaged it permeating the whole of the Brothers’ day. Later the Institute recieved, at the request of Fr. Peter Kenney, a Rescript from Pope Pius VIII privileging this community greeting. It granted “all and each of the Indulgences and Favours already granted to a similar Congregation existing in France” including “a Plenary Indulgence... for the pious practice of reciting according to rule “Live, Jesus, in our hearts forever” forty days’ Indulgence for every time the Brothers pronounce those holy words".

Influence of the De La Salle Rule

We know that after 1817 Edmund and his Brothers were in contact with the French de la Salle tradition, their Rules and devotional traditions as well as their educational practices. Apart from the explicit theology of one chapter on the Spirit of the Institute, the French rules were largely legalistic in tone, so while the general structure and layout of the De la Salle rule was kept, the Irish Brothers made profound changes, as their French counterparts later acknowledged.

Ninety four of the French Constitutions were incorporated unchanged, namely those concerning the structures of community and school, and those that were in harmony with the spirituality of Edmund and the Irish Brothers. In general, there is a broader, more mature vision of religious responsibility and many Constitutions involving minutiae of conduct were omitted. The wording of 24 borrowed Constitutions were altered and 66 new Constitutions were added. The specific character of Edmund's new Rule is important, especially Chapter One (The end of the Institute), Two (The Spirit of the Institute) and Three (Pious Exercises). Many aspects of Edmund’s own character and spirituality, and that of his first followers, along with traditional Irish customs, are seen in the prescriptions that would regulate the lives of the Brothers.

Influence of the Jesuits

Edmund’s choice of Ignatius as a religious name in 1809, in preference to local saints like Declan or Kieran, illustrates the extent to which his spirituality was being shaped by the Jesuits and the European Catholic Reformation. He also included the Jesuit banner “Ad Majorem dei Gloriam” on the frontispiece of the printed Presentation Rule in 1802, and the Brothers were to recite the short Office of our Blessed Lady which the early Jesuits had promoted among the literate laity. An Ignatian thrust was further evident where the Rule advocated the annual “Spiritual Exercises”, annual retreats and monthly days of recollection, as well as commending daily mental prayer or meditation, recommended in the writings of Lorenzo Scupoli and by St. Ignatius. Before 1832 Fr. Kenny gave Edmund an English translation of the Jesuit Summary of the Constitutions which became the source for the direct borrowings from Jesuit rules found in the first two chapters of the 1832 Rule. It is presupposed that Fr. Kenney and other Jesuit friends of Edmund advised in the sensitive incorporation of this material related to the apostolic character of the new Institute.

Given the network of Irish Colleges, training Irish students for the priesthood, in Europe at this time (established in Lisbon 1590, Salamanca 1592, Santiago de Compostela 1605, Seville 1608, Rome 1628 and Poitiers 1674), sveral of them Jesuit-led institutions, it is unsurpising that European ideas were making their way back to Ireland. Edmund's close friendship with several Jesuits ensured he was well aware of the latest developments.

We are aware also of the circulation of popular religious translations in Ireland at that time. These helped to establish links to the global Catholic community. We know Edmund was an avid reader and purchased copies of various books for himself and for the Brothers’ communities, including three copies of The Interior Christian by Jean de Bernières Louvigny which he bought in 1804, The Practice of Christian Perfection by Fr. Rodriguez SJ which he bought in 1806, and The Spiritual Combat by Dom Lorenzo Scupoli, this "golden book" as Francis de Sales called it, and a copy of which Francis carried in his pocket for 18 years – one which he himself had received from Fr. Scupoli in Padua.

a) God before all else

The 1802 Rule stated: “God, and God alone, must be the principal motive and end of all their actions. It is this pure intention of pleasing God that characterizes the good work and renders it valuable and meritorious. Without it, the most laborious functions of the Institute, the greatest austerities, the most heroic actions and sacrifices are of little value, and are divested of that merit which flows from pure and upright intention; while, on the contrary, accompanied by it, actions the most trivial and insignificant in themselves become virtuous, valuable and meritorious of eternal life” .

The 1802 Rule: “The Brethren of this Congregation shall rise, every morning, winter and summer, at five o'clock, making the sign of the Cross on themselves and giving their first thought to God” .

With the pupils in the schools, “They shall instruct them how to offer all their thoughts, words, and works to God's glory; implore his grace to know and to love him, and to fulfil his commandments” .

Regarding the novice master: “He shall impress on their minds that, by the virtue of obedience, the religious soul becomes most intimately united to God; that the will of God so governs and directs such souls, as to entitle them to say with the Apostle, ‘They live - and yet live not - but Christ liveth in them’; that it is God that then regulates all their steps, words, prayers, lectures, recreation, and every work and action of their lives”

b) The Imitation of Christ, Divine Model

At the core of his spirituality, Edmund believed that to follow Christ was to centre one's life on Him, to take up his way of life, to adopt his interior attitudes and to imitate his actions. This way of understanding discipleship has its origins in the New Testament: “Be imitators of me as I am of Christ” (1 Cor. 11:1), as well as in the Celtic tradition going back to St. Patrick who fused the practice of recollection in the Lord with one of a purity of intention - a spirit of prayer which for Edmund became the soul of a life of opening himself to the spirit and committing himself to devoted service.

From the opening words of his 1802 Rule we see this focus placed before the first Brothers: “the Brethren whom God is graciously pleased to call to this state of perfection shall encourage themselves and animate their fervour and zeal by the example of their Divine Master, who testified on all occasions a tender love for little children”

The 1802 Rule: “The Brethren of this pious Institute formed and grounded on charity should make that favourite virtue of their Divine Master their own most favourite virtue. This they should study to maintain and cherish so perfectly among themselves as to live together as if they had but one heart and one soul in God”.

“The perfection of the religious soul depends not so much in doing extraordinary actions, as on doing extraordinarily well the ordinary actions and exercises of every day”.

“This Congregation is in a special manner founded on Mount Calvary, there to serve a crucified Jesus, by whose example the Brethren ought to crucify their senses, imaginations, passions, inclinations, aversions and caprices for the sake and love of their Divine Master”.

c) The Eucharist and Visits to the Blessed Sacrament

There was a particular devotion to the presence of Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament in the Rule, a hallmark of Edmund’s spirituality and in line with the teachings of the Council of Trent. Throughout his life Edmund was known for his personal devotion to the eucharist and the Blessed sacrament, attending daily morning Mass as a businessman in St. Patrick's Church in Waterford

The day was punctuated with frequent visits to the oratory. In Edmund's vocation, the Eucharist occupies a central place. The Eucharist was his preferred place for remembering people in prayer. Here he was united to the love to Christ and to people in such a way that that these people are loved in the Lord. Edmund saw the Eucharist as an affective place where he was mindful of the Brothers and prayed for them.

The 1802 Rule: “Jesus Christ present in the most holy Eucharist shall also be the object of their tenderest affection and devotion. They shall often reflect on the infinite charity he displays for them in that ever adorable Sacrament, and by frequent visits every day, they shall pay assiduous court to their heavenly King on the throne of his love”

The 1802 Rule: “The most holy Eucharist having been instituted by Jesus Christ for the nourishment of our souls as well as for our sacrifice, and as in it he imparts to us the most precious pledge of his love, the Brethren shall cherish the tenderest and most affectionate devotion towards this adorable Sacrament”.

d) Mental Prayer and Scripture Reading

The 1802 Rule states “Mental prayer, or meditation, has ever been considered most effectual to imprint deeply on the mind the sublime truths of religion, to elevate the soul, and inflame the heart with the love of God and of heavenly things… The Brethren of this Congregation shall, therefore, most sedulously attend to this holy exercise; in this they shall take delight, and seek their comfort and refreshment from the labours and fatigues of the Institute”.

Edmund had purchased a Douay Bible (McMahon edition) in 1791 (and, in 1818, a McNamara edition) and was known for spendinging significant time daily reading the scriptures. In the 1832 Rule we see his devotion to Scriptures in the scripture quoted in the text, but also woven into the fibre of the text, especially in chapter 2.

Awareness of the presence of God, a significant element of Edmund’s spirituality, was exemplified in the practice of prayer in the first schools, an effective means of being mindful of the presence of God, and also a practical example of docility to grace.

The 1802 Rule states “At twelve o'clock the Angelus, with the acts of Contrition, Faith, Hope and Charity shall be said, with a few Paters and Aves, not exceeding five, for such particular intentions as the circumstances of the time or the devotion of the Brother who delivers the instructions may suggest. At three, the Litany of our Blessed Lady, with the Salve Regina, shall be said to recommend themselves to her holy protection, after which the children shall be dismissed, and school broken up”.

A spirit of prayer breathes through all the prescriptions of the 1832 Rule, whether it be dealing with house, school, travelling, writing, celebrations or day-to-day living. The tradition in Mount Sion remembered Edmund’s great spirit of prayer. The importance of silence and recollection as providing the necessary atmosphere for prayer is stressed throughout the Rule, stemming probably from their experience of two decades of living in community under the old Rule.

e) Love for Mary, the Mother of Jesus

The 1802 Rule states “As this Society is immediately under her special protection; as she, next to God, is its principal patroness and protectress, the Brethren shall have the warmest and most affectionate devotion to her, regarding her in a special manner as their Mother, and the great model they are obliged to imitate; that by her intercession and powerful protection they may be enabled to fulfil the obligations of their holy Institute, and implant Jesus Christ in the tender hearts of those dear little ones whom they are charged to instruct”.

The 1832 Rule prescribed Marian devotions for the Brothers and brought Our Lady into the classrooms. The Memorare had always been a favourite prayer of Edmund.