1779 Edmund enters business with his uncle in Waterford

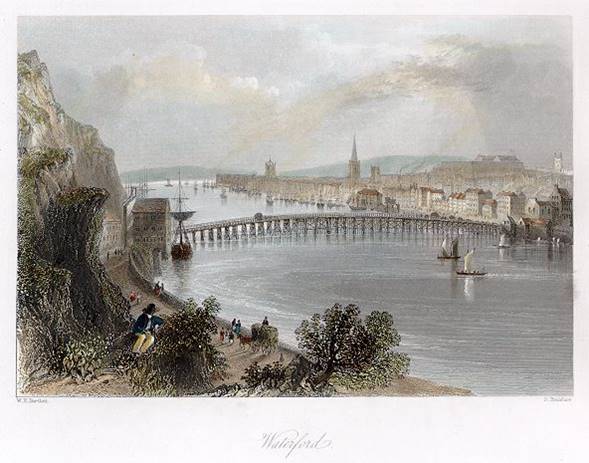

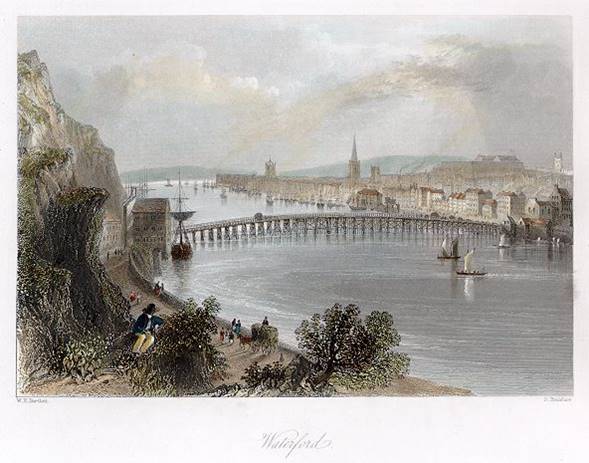

Edmund Rice arrived in Waterford in 1779. As there was no bridge across the river Suir, he would have taken the ferry from the Kilkenny side into the city.

Edmund Rice arrived in Waterford in 1779. As there was no bridge across the river Suir, he would have taken the ferry from the Kilkenny side into the city.

By the mid eighteenth century, Waterford was a city with a thriving port and centre for the processing of the tillage and dairying produce of its hinterland. It manufactured and shipped goods to Newfoundland, England and mainland Europe. By the time Edmund Rice moved to Waterford the port traded in a wide range of goods such as butter, flour, sugar, salted beef and bacon, tea, coffee, beer, whiskey, tallow, hemp, dried fish, cod oil, spices, soap, timber, pitch and tar. The Protestant Ascendancy held trade in contempt and this facilitated the upward mobility of Catholic merchants at a time when the law didn't permit them to buy land or take long leases.

The quay impressed visitors to Waterford. In 1746 it was described as: "about half a mile in length and of considerable breadth, not inferior to but rather exceeds the most celebrated in Europe. To it the largest trading vessels may conveniently come up, both to load and unload... The Exchange, Custom House and other public buildings, ranged along the quay are no small addition to its beauty" (C. Smith).

Lewis' Topographical Survey (1837) tells us a lot about Waterford ass a city of maritime trade and commerce:

Lewis' Topographical Survey (1837) tells us a lot about Waterford ass a city of maritime trade and commerce:

"On an average of three years from 1831 to 1834, the quantity of provisions exported annually was, 38 tierces of beef, 880 tierces and 1795 barrels of pork, 392,613 flitches of bacon, 13,284 cwt of butter, 19,139 cwt. of lard, 152,1I3, barrels of wheat, 160,954 barrels of oats, 27,045 barrels of barley, 403,852 cwt. of flour, 18,640 cwt. of oatmeal, and 2857 cwt of bread.

Of livestock the number annually exported, during the same period, was, on an average, 44,241 pigs, 5808 head of cattle, and 9729, sheep; the aggregate value of all which, with the provisions, amounted to £2,209,668.

The principal imports are tobacco, sugar, tea, coffee, pepper, tallow, pitch and tar, hemp, flax, wine, iron, potashes, hides, cotton, dye-stuffs, timber, staves, saltpetre, and brimstone, from foreign ports; and coal, calm, soap, iron, slate, spirits, printed calico, earthenware, hardware, crown and window glass, glass bottles, bricks, tiles, gun-powder, and bark, from the ports of Great Britain.

The gross estimated value of the imports in a recent year was £1,274,154, whereof £66,630 were for coal, slates, &C.; £27,659 iron and other metals, hardware, this improvement amounted to £21,901, towards which machinery, &c.; £665,386 woollens, cottons, silks, &c.; government contributed £14,588, and the remainder £153,667 tea, coffee, and sugar; £5750 wines; was paid from duties levied on the shipping under £102,900 tobacco; and the remainder in various other."

Edmund was to become an apprentice to his uncle Michael Rice, 'a victualler and ship chandler', ran a business in Barronstrand Street exporting goods to Bristol and supplying some of the 1,000 ships that sailed into waterford each year with everything needed for long trips at sea - including cured meats, sail-cloth, cords, ropes, oil, biscuits and salt. The French Wars, after 1793, brought a great boom in supplying beef and pork. Quickly Edmund learnt the tricks of this trade and took to the business side of things. He had an eye for detail and a wonderful way with people.

Waterford was the second largest port in all Europe at this time, but this attracted many poor people from the countryside, driven from their land, and hoping to gain some kind of livelihood even if it was from begging in the city.

Living with his uncle at Arundel Place, just off the quays, Edmund had to adjust to his new life in Waterford now that he was earning money and having a good deal or freedom. It seems he was not always exemplary, for it was reported of him on a visit back to his home in Callan, that an old poet, James Phelan of Coolagh, met young Rice after Mass in the parish church and chided him for some misconduct in the church. Edmund was told in no uncertain terms that his attitude in the House of God was unbecoming of a Catholic. To his credit Edmund took this admonition to heart, and the remarks had a very steadying effect on him. (ref. John Shelly in Memories)

Rather enigmatically Maurice Lenihan, editor of The Tipperary Vindicator, wrote of Edmund at the time of his death, and after he had very generously praised him: “We believe that Mr. Rice’s early life had not given promise of that religious earnestness which he (later) began to display”. It would certainly not be an exaggeration to say that Edmund went through some kind of “conversion” at this stage of his life.

According to Houlihan, young Edmund Rice was to become one of waterford's most successful and respected citizens. It did not take him long to set his roots down in the city that would be his home for the next 65 years. Fresh from his training at the academy in Kilkenny, Edmund was welcomed by his uncle Michael Rice who had two sons of his own and who treated his nephew as if he were a third son. Edmund threw himself into the work at his uncle’s provisioning company and Michael Rice was quite happy to have his help in managing his prosperous concern, especially since neither of his sons was interested in this type of work. Edmund’s organizing skills and his ability to work well with others resulted in expanding and making many improvements so that profits continued to mount. “Soon Edmund became a familiar figure in his uncle’s stores in Baronstrand Street, the warehouses on the quay, on board ship, or as he rode on horseback to buy cattle and farm produce to stock the ships in Waterford Harbour. He quickly won his uncle’s confidence, and a deep affection grew up between them. The business thrived.” (ref. Blake)

At Westcourt, his mother and father were proud of their son the young merchant. They knew that his uncle was very satisfied with him and that recommendation was good enough for them. In September, 1787, Mr. Robert Rice, Edmund’s father, drew up his will and to the amazement of no one in the family, he appointed Edmund executor. This made Edmund the legal head of the family. Robert Rice knew all of his sons very well and considered Edmund to be the one to take charge of things when he had passed away. The will provided for his ‘dearly beloved wife Margaret’, that she would have the home at Westcourt. There were provisions for each family member. Land records show that Edmund purchased his brothers’ shares of the land in due course. “It was a measure of the trust his father placed in Edmund, that he was made executor of the will. This was a delicate matter and demanded efficiency and integrity.” (ref. Normoyle) A few years later Edmund would also administer the last will of his youngest brother, Michael, who died in Waterford. With good reason, his parents and his siblings had confidence in their son and brother.

But there was much more to Edmund Rice than business acumen. He was a devout Catholic layman who made no secret about his love for the Church and all it stood for. His daily routine began with attendance at Mass in St. Patrick's chapel near his home, and even though it was quite uncommon among Catholics of the day, he frequently received communion. Though the Jesuis had been suppressed and finally abolished by the Holy See in 1773, Edmund was in contact with several Jesuits who he knew, and after the restoration of the Jesuits in 1811, several of his prominent spiritual mentors were members of the Order.

But there was much more to Edmund Rice than business acumen. He was a devout Catholic layman who made no secret about his love for the Church and all it stood for. His daily routine began with attendance at Mass in St. Patrick's chapel near his home, and even though it was quite uncommon among Catholics of the day, he frequently received communion. Though the Jesuis had been suppressed and finally abolished by the Holy See in 1773, Edmund was in contact with several Jesuits who he knew, and after the restoration of the Jesuits in 1811, several of his prominent spiritual mentors were members of the Order.

He belonged to a group of Catholic young men, most of them fellow-merchants, who were devoted to developing their spiritual lives and to performing good works. They met on a regular basis and committed themselves to works of charity, especially among the abjectly poor of the area. Edmund soon found himself involved with several other local agencies that provided social services to people in need. He used all of his business skills to see to it that the poor would receive whatever kind of aid they needed. He had a special interest in the homeless, in orphans, in widows, in anyone who needed assistance of any kind. He took on the role of advocate in upholding the legal rights of those who were not able to fend for themselves in a society that looked down on Catholics, especially the poor.

Although in the early 1800's Waterford city was experiencing a wave of prosperity it had never known before, it also had a slum area which was home to many of its people and where living conditions were the lowest of the low. Jobs were scarce for Catholic men. What little income that did come their way was often spent in the pubs and grog shops. A professional traveller to Waterford at this time commented: “Whiskey drinking prevails to a dreadful extent in Waterford. There are between two and three hundred licensed houses; and it certainly does seem to me that among the remedial measures necessary for the tranquillity and happiness of Ireland, an alteration in the licensing system is one of the most important.” (ref. Inglis)

At this period of his life, Edmund Rice seemed to be living two lives. By day he was in his working place pouring all of his energy into managing his uncle’s firm. After hours, he was equally occupied, this time being the agent of the homeless, the rejected, the widows, orphans, street urchins, debtors or any person who sought his help. He obtained and delivered food, bedding, fuel and medicine to the needy and tried to find lodgings for those who had no homes. He became a member of several other charitable committees in order to obtain funds from various sources to support families or individuals who had no other means at their disposal. Once he joined these committees, he usually became an officer so that he could use his influence to urge the societies to increase their efforts. At times he would challenge the banks and trusts that were not prompt in paying interest to the beneficiaries of wills — usually homes for orphans, for senior citizens or other impoverished people. He became an expert in the legal procedures needed to expedite payments to such causes.

Edmund was fast becoming one of the leading citizens of Waterford. His business associates respected him for his brilliant management, for his new ideas and for his integrity in all of his affairs. He was regarded as an exemplary Catholic layman. The bishop and priests relied on him to advise them in financial matters, especially in regard to real estate. The poor looked to him as a friend and benefactor who worked tirelessly for them and their needs. He was befriended by many of the best families in Waterford and he was able to convince some of them to join him on the several committees to which he belonged as they were always in need of donations and volunteers. One of his closest associates, Brother Austin Dunphy, tells us that “Edmund Rice was one of the very few persons who was allowed to pass unchallenged at all the military posts in Waterford, Carrick-on-Suir, Clonmel, Tipperary and Limerick.” (ref. Fitzpatrick) The obvious inference from this statement is that Edmund Rice was so well known, trusted and respected at the military posts, because of his business contacts with them supplying meat, butter, cattle, sheep, oats, hay, straw, etc. that he was most reliable and consequently one of the most trusted of civilians who had access to the military authorities.

Edmund was fast becoming one of the leading citizens of Waterford. His business associates respected him for his brilliant management, for his new ideas and for his integrity in all of his affairs. He was regarded as an exemplary Catholic layman. The bishop and priests relied on him to advise them in financial matters, especially in regard to real estate. The poor looked to him as a friend and benefactor who worked tirelessly for them and their needs. He was befriended by many of the best families in Waterford and he was able to convince some of them to join him on the several committees to which he belonged as they were always in need of donations and volunteers. One of his closest associates, Brother Austin Dunphy, tells us that “Edmund Rice was one of the very few persons who was allowed to pass unchallenged at all the military posts in Waterford, Carrick-on-Suir, Clonmel, Tipperary and Limerick.” (ref. Fitzpatrick) The obvious inference from this statement is that Edmund Rice was so well known, trusted and respected at the military posts, because of his business contacts with them supplying meat, butter, cattle, sheep, oats, hay, straw, etc. that he was most reliable and consequently one of the most trusted of civilians who had access to the military authorities.

For entertainment Edmund enjoyed Irish dancing, songs and music that were traditionally a part of the culture. It is recorded of him that on occasional Sunday afternoons, Edmund took a stroll from the city out to the suburbs to a place known as “the Yellow House Inn." He enjoyed meeting his friends there and was especially happy to hear his favourite music and to join in the choruses or to participate in one of the dances or reels. A Thomas Moore song that he liked to sing “Oh! Had We Some Bright Little Isle of Our Own” was one of the popular songs of the day. Years later as a Christian Brother “Edmund had a great fund of stories that enlivened community recreation and a droll sense of humour that brought many a laugh. Sometimes, especially on festive occasions, the brothers had a concert when Edmund would join with them in singing his favourite songs from Moore's Irish Melodies?” (ref. Normoyle)

Edmund was constantly travelling to fairs and markets on horseback, negotiating the sale of pigs and cattle from farmers to fulfil his contractual obligations for the British military. He walked through all the counties on Munster and beyond it, covering as many as possible of the four and a half thousand fairs that were held annually at the time. It is not surprising that later in 1818, during Rice’s conflict with Bishop Walsh, Rice’s clerical enemies described him as “this man sometimes was a dealer in cattle and a common butcher in the streets of Waterford."

Edmund was constantly travelling to fairs and markets on horseback, negotiating the sale of pigs and cattle from farmers to fulfil his contractual obligations for the British military. He walked through all the counties on Munster and beyond it, covering as many as possible of the four and a half thousand fairs that were held annually at the time. It is not surprising that later in 1818, during Rice’s conflict with Bishop Walsh, Rice’s clerical enemies described him as “this man sometimes was a dealer in cattle and a common butcher in the streets of Waterford."

It is accurate to conclude that the intermittent hostilities England pursued with republican France and its need to provide for garrisoned troops throughout Ireland meant prosperity for the young victualler. Indeed, there were over 20,000 soldiers in over 100 barracks in the country during this time. (see McLoughlin pp19-26)

The Rices of Munster are almost entirely of Welsh origin, where the commonest forms were Reece, Ruys and Rhys. This family had entered England with William the Conqueror in 1066. Several of these families came to Ireland and settled on the southern coast particularly in Waterford, Kerry and to a less extent in Cork. There are indications that the Waterford Rices moved north towards Kilkenny. The Red Book of Ormond, giving the extent of the Manor of Knocktopher on 23 July 1312, records the names of Philip, William, John and Matthew Rys. The Calendar of Ormond Deeds mentions that near Knocktopher there “is a townland of Riceslands called from the family of Rys or Rice.” Moreover a James Rice was a Burgher of Kilkenny in 1383 and a Gilbert Rice was a member of Kilkenny Council in 1434. It is thus clear that the name Rice was well established in Kilkenny and district from the fourteenth century.

The Rices of Munster are almost entirely of Welsh origin, where the commonest forms were Reece, Ruys and Rhys. This family had entered England with William the Conqueror in 1066. Several of these families came to Ireland and settled on the southern coast particularly in Waterford, Kerry and to a less extent in Cork. There are indications that the Waterford Rices moved north towards Kilkenny. The Red Book of Ormond, giving the extent of the Manor of Knocktopher on 23 July 1312, records the names of Philip, William, John and Matthew Rys. The Calendar of Ormond Deeds mentions that near Knocktopher there “is a townland of Riceslands called from the family of Rys or Rice.” Moreover a James Rice was a Burgher of Kilkenny in 1383 and a Gilbert Rice was a member of Kilkenny Council in 1434. It is thus clear that the name Rice was well established in Kilkenny and district from the fourteenth century.

Westcourt, the family home and farmstead of the Rice family, was a peaceful place when compared to most of the houses in the town of Callan. The family home was quite large, although with nine children, Robert and Margaret Rice needed every bit of space to accommodate all of them. It contained four bedrooms, a parlour, a kitchen and a hallway. There were other farm buildings on the property and a number of small houses for the hired men and their families.

Westcourt, the family home and farmstead of the Rice family, was a peaceful place when compared to most of the houses in the town of Callan. The family home was quite large, although with nine children, Robert and Margaret Rice needed every bit of space to accommodate all of them. It contained four bedrooms, a parlour, a kitchen and a hallway. There were other farm buildings on the property and a number of small houses for the hired men and their families. Edmund Rice arrived in Waterford in 1779. As there was no bridge across the river Suir, he would have taken the ferry from the Kilkenny side into the city.

Edmund Rice arrived in Waterford in 1779. As there was no bridge across the river Suir, he would have taken the ferry from the Kilkenny side into the city. Lewis' Topographical Survey (1837) tells us a lot about Waterford ass a city of maritime trade and commerce:

Lewis' Topographical Survey (1837) tells us a lot about Waterford ass a city of maritime trade and commerce: But there was much more to Edmund Rice than business acumen. He was a devout Catholic layman who made no secret about his love for the Church and all it stood for. His daily routine began with attendance at Mass in St. Patrick's chapel near his home, and even though it was quite uncommon among Catholics of the day, he frequently received communion. Though the Jesuis had been suppressed and finally abolished by the Holy See in 1773, Edmund was in contact with several Jesuits who he knew, and after the restoration of the Jesuits in 1811, several of his prominent spiritual mentors were members of the Order.

But there was much more to Edmund Rice than business acumen. He was a devout Catholic layman who made no secret about his love for the Church and all it stood for. His daily routine began with attendance at Mass in St. Patrick's chapel near his home, and even though it was quite uncommon among Catholics of the day, he frequently received communion. Though the Jesuis had been suppressed and finally abolished by the Holy See in 1773, Edmund was in contact with several Jesuits who he knew, and after the restoration of the Jesuits in 1811, several of his prominent spiritual mentors were members of the Order. Edmund was fast becoming one of the leading citizens of Waterford. His business associates respected him for his brilliant management, for his new ideas and for his integrity in all of his affairs. He was regarded as an exemplary Catholic layman. The bishop and priests relied on him to advise them in financial matters, especially in regard to real estate. The poor looked to him as a friend and benefactor who worked tirelessly for them and their needs. He was befriended by many of the best families in Waterford and he was able to convince some of them to join him on the several committees to which he belonged as they were always in need of donations and volunteers. One of his closest associates, Brother Austin Dunphy, tells us that “Edmund Rice was one of the very few persons who was allowed to pass unchallenged at all the military posts in Waterford, Carrick-on-Suir, Clonmel, Tipperary and Limerick.” (ref. Fitzpatrick) The obvious inference from this statement is that Edmund Rice was so well known, trusted and respected at the military posts, because of his business contacts with them supplying meat, butter, cattle, sheep, oats, hay, straw, etc. that he was most reliable and consequently one of the most trusted of civilians who had access to the military authorities.

Edmund was fast becoming one of the leading citizens of Waterford. His business associates respected him for his brilliant management, for his new ideas and for his integrity in all of his affairs. He was regarded as an exemplary Catholic layman. The bishop and priests relied on him to advise them in financial matters, especially in regard to real estate. The poor looked to him as a friend and benefactor who worked tirelessly for them and their needs. He was befriended by many of the best families in Waterford and he was able to convince some of them to join him on the several committees to which he belonged as they were always in need of donations and volunteers. One of his closest associates, Brother Austin Dunphy, tells us that “Edmund Rice was one of the very few persons who was allowed to pass unchallenged at all the military posts in Waterford, Carrick-on-Suir, Clonmel, Tipperary and Limerick.” (ref. Fitzpatrick) The obvious inference from this statement is that Edmund Rice was so well known, trusted and respected at the military posts, because of his business contacts with them supplying meat, butter, cattle, sheep, oats, hay, straw, etc. that he was most reliable and consequently one of the most trusted of civilians who had access to the military authorities. Edmund was constantly travelling to fairs and markets on horseback, negotiating the sale of pigs and cattle from farmers to fulfil his contractual obligations for the British military. He walked through all the counties on Munster and beyond it, covering as many as possible of the four and a half thousand fairs that were held annually at the time. It is not surprising that later in 1818, during Rice’s conflict with Bishop Walsh, Rice’s clerical enemies described him as “this man sometimes was a dealer in cattle and a common butcher in the streets of Waterford."

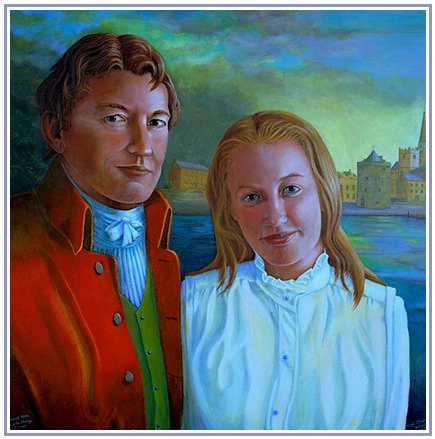

Edmund was constantly travelling to fairs and markets on horseback, negotiating the sale of pigs and cattle from farmers to fulfil his contractual obligations for the British military. He walked through all the counties on Munster and beyond it, covering as many as possible of the four and a half thousand fairs that were held annually at the time. It is not surprising that later in 1818, during Rice’s conflict with Bishop Walsh, Rice’s clerical enemies described him as “this man sometimes was a dealer in cattle and a common butcher in the streets of Waterford." According to Garvan, after some years in Waterford Edmund met Mary Elliott whom he came to love deeply. She came from a well-to-do family. Shortly after the death of his uncle, when he had taken over the family business, Edmund asked Mary to marry him and in 1785 they were united in matrimony. He was 23 years old. They lived in the part of Waterford called Ballybricken. All this time Edmund’s business experience was growing and he was outstandingly successful because of his intelligence, acumen, integrity, qualities of leadership, and especially his ability to get on with people. Mary shared in Edmund’s happiness, the more so because she could also rejoice in his continuing compassion for the poor. But their happiness was not without its sadness because Edmund’s father died in November 1787. Interestingly, Robert Rice made Edmund an executor of his will even though he was the fourth son.

According to Garvan, after some years in Waterford Edmund met Mary Elliott whom he came to love deeply. She came from a well-to-do family. Shortly after the death of his uncle, when he had taken over the family business, Edmund asked Mary to marry him and in 1785 they were united in matrimony. He was 23 years old. They lived in the part of Waterford called Ballybricken. All this time Edmund’s business experience was growing and he was outstandingly successful because of his intelligence, acumen, integrity, qualities of leadership, and especially his ability to get on with people. Mary shared in Edmund’s happiness, the more so because she could also rejoice in his continuing compassion for the poor. But their happiness was not without its sadness because Edmund’s father died in November 1787. Interestingly, Robert Rice made Edmund an executor of his will even though he was the fourth son.

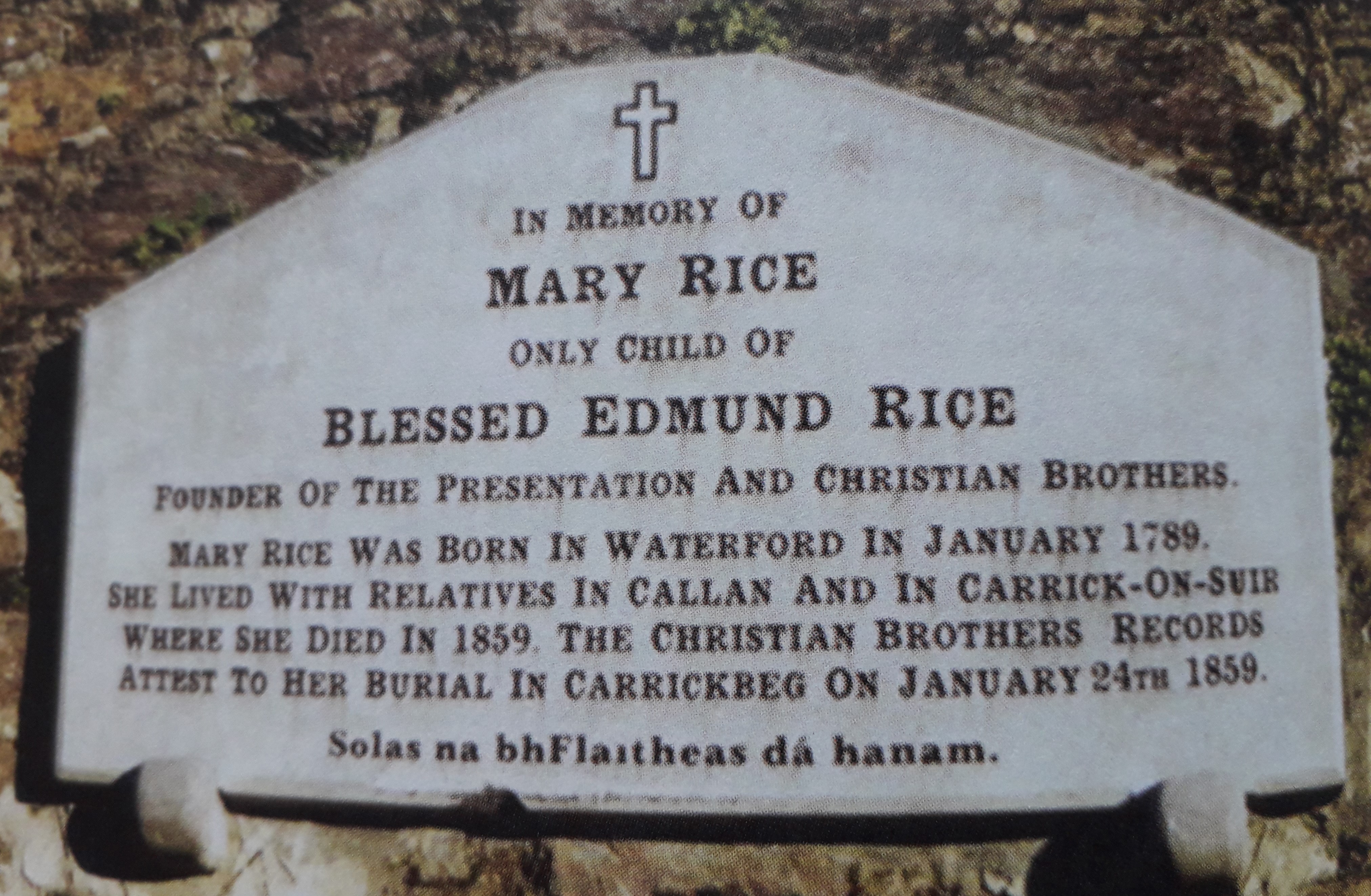

The reference to Mrs. Rice's death appeared in newspapers for January 17, 1789 and the place of her burial is unknown. Edmund was 26 years old and the widowed father of an infant girl.

The reference to Mrs. Rice's death appeared in newspapers for January 17, 1789 and the place of her burial is unknown. Edmund was 26 years old and the widowed father of an infant girl. No doubt, the single father shared with Joan the feeding, bathing and toilet training of young Mary, guided her first tenuous steps at walking and encouraged her experimenting with talking. Did he especially treasure that day when Mary attempted to call him ‘Dada’?...

No doubt, the single father shared with Joan the feeding, bathing and toilet training of young Mary, guided her first tenuous steps at walking and encouraged her experimenting with talking. Did he especially treasure that day when Mary attempted to call him ‘Dada’?... The first of many legal bequests for which Edmund became responsible was in connection with the Will of his father. Though a young man at the time of his father's death, he was the one, rather than any of his three older brothers, selected by Robert Rice to be the Executor of his Will. Soon afterwards he became involved in buying a plot of land for three Waterford women who had gone to Cork to join the Presentation Sisters, in anticipation of their return to establish a school for poor girls in 1800. Upon their return Edmund also became the Trustee of their dowries. In Thurles he became involved, with Archbishop Bray, in securing the bequest of the former Bishop, Dr. Butler, for the Presentation Sisters there.

The first of many legal bequests for which Edmund became responsible was in connection with the Will of his father. Though a young man at the time of his father's death, he was the one, rather than any of his three older brothers, selected by Robert Rice to be the Executor of his Will. Soon afterwards he became involved in buying a plot of land for three Waterford women who had gone to Cork to join the Presentation Sisters, in anticipation of their return to establish a school for poor girls in 1800. Upon their return Edmund also became the Trustee of their dowries. In Thurles he became involved, with Archbishop Bray, in securing the bequest of the former Bishop, Dr. Butler, for the Presentation Sisters there.

According to O'Dwyer

According to O'Dwyer  According to Houlihan, Edmund, being a young man without a wife and with an infant who needed extraordinary attention and care, was forced in his desolation to re-think his options for the years that lay ahead. He did not panic, nor did he lose confidence in a provident God.

According to Houlihan, Edmund, being a young man without a wife and with an infant who needed extraordinary attention and care, was forced in his desolation to re-think his options for the years that lay ahead. He did not panic, nor did he lose confidence in a provident God.

The Presentation Sisters had been founded in Cove Lane, Cork, in 1775 by Nano Nagle to educate girls.

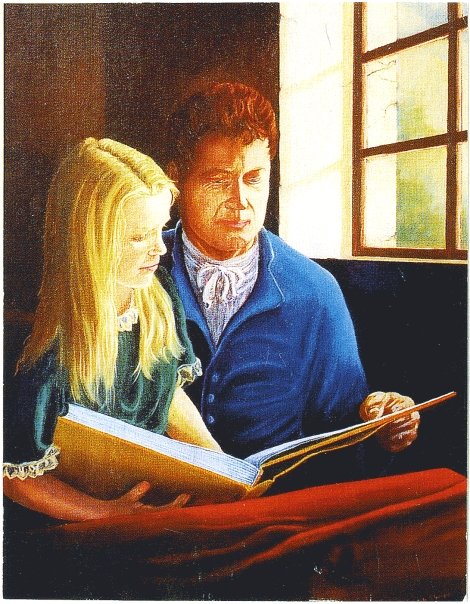

The Presentation Sisters had been founded in Cove Lane, Cork, in 1775 by Nano Nagle to educate girls. One account narrates that to his step-sister, Joan Murphy, he expressed the intention of going to Europe for this purpose (of entering a monastery). She said: “It would be better for you to stay at home and devote yourself and your money to educating and instructing Irish boys”.

One account narrates that to his step-sister, Joan Murphy, he expressed the intention of going to Europe for this purpose (of entering a monastery). She said: “It would be better for you to stay at home and devote yourself and your money to educating and instructing Irish boys”. For these reasons, Joan seems to be the most likely Waterford lady who would have acted as his personal confidante in his decision making. This matter is inconclusive and clearly open to debate. Nevertheless, it should be recalled that this consultation occurred sometime in 1793 or 1794, for, supposedly having gained Joan’s positive counsel, Rice sought ecclesial advice from Bishop James Lanigan in 1794.

For these reasons, Joan seems to be the most likely Waterford lady who would have acted as his personal confidante in his decision making. This matter is inconclusive and clearly open to debate. Nevertheless, it should be recalled that this consultation occurred sometime in 1793 or 1794, for, supposedly having gained Joan’s positive counsel, Rice sought ecclesial advice from Bishop James Lanigan in 1794. What does seem likely is that the ‘delicate’ Mary was at an age and of sufficient capacity to proyide real assistance to young Mrs Richard Rice with a rapidly expanding young family. So it is proposed that Richard broached the issue with Edmund about Mary becoming part of his family to assist him and his wife care for her many younger cousins.

What does seem likely is that the ‘delicate’ Mary was at an age and of sufficient capacity to proyide real assistance to young Mrs Richard Rice with a rapidly expanding young family. So it is proposed that Richard broached the issue with Edmund about Mary becoming part of his family to assist him and his wife care for her many younger cousins. According to Houlihan, with the funds obtained from the sale of his provisioning concern, Edmund Rice purchased a plot of land on the south side of Waterford. This was close to the Ballybricken home where he had lived with his wife for those few years they enjoyed together. Nor was it far from the Presentation Nuns whom he had helped with the establishing of their convent and school. In fact there was a narrow passageway known as “Hennessy’s Lane” connecting the two properties so that Edmund and his community could use this pathway to go to the convent for daily Mass. Brother Rice's new school would be on an elevated site in the working-class district where once the thatched Faha chapel had stood.

According to Houlihan, with the funds obtained from the sale of his provisioning concern, Edmund Rice purchased a plot of land on the south side of Waterford. This was close to the Ballybricken home where he had lived with his wife for those few years they enjoyed together. Nor was it far from the Presentation Nuns whom he had helped with the establishing of their convent and school. In fact there was a narrow passageway known as “Hennessy’s Lane” connecting the two properties so that Edmund and his community could use this pathway to go to the convent for daily Mass. Brother Rice's new school would be on an elevated site in the working-class district where once the thatched Faha chapel had stood.

James O'Rourke of Peter St, Waterford recalled in 1912:

James O'Rourke of Peter St, Waterford recalled in 1912: One constant reality that surrounded Edmund during his life was famine and famine fever. There was dysentery, typhoid, typhus, hunger and disease all around. These evils were the fruits of injustice, of political and historical circumstances. Official commissions investigating the conditions of prisons in Edmund’s time produced horrifying reports of suffering, misery, disease, severity, punishments and violence. Death sentences were common in those days and we know that, for example, some 130 persons were hanged in Co. Cork between 1767 and 1806 – 32 for murder and 98 for theft – while 202 were transported.

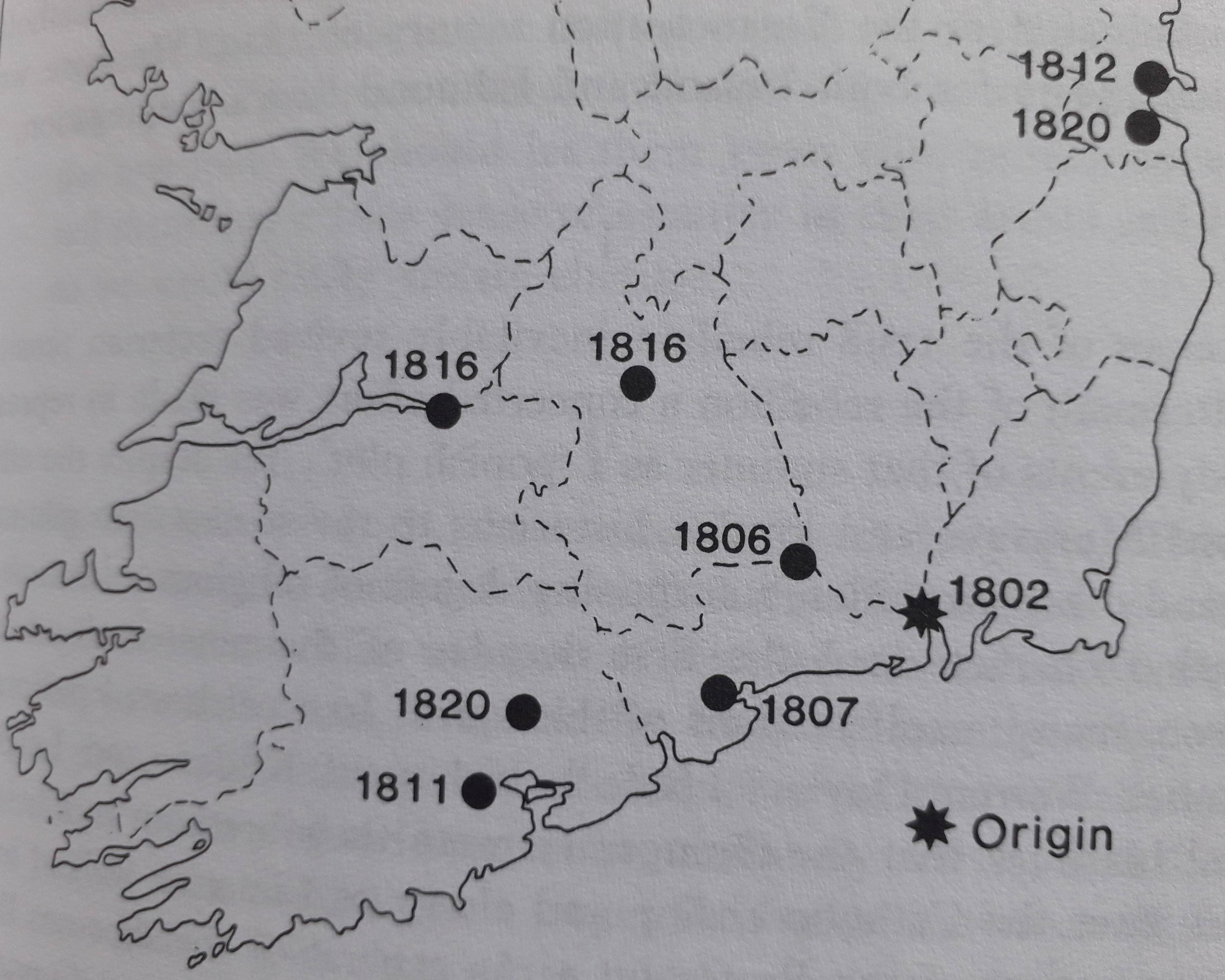

One constant reality that surrounded Edmund during his life was famine and famine fever. There was dysentery, typhoid, typhus, hunger and disease all around. These evils were the fruits of injustice, of political and historical circumstances. Official commissions investigating the conditions of prisons in Edmund’s time produced horrifying reports of suffering, misery, disease, severity, punishments and violence. Death sentences were common in those days and we know that, for example, some 130 persons were hanged in Co. Cork between 1767 and 1806 – 32 for murder and 98 for theft – while 202 were transported. According to Houlihan, as news of the success of Mount Sion was spread around Waterford, and as the school was expanding, in order to accommodate incoming students, Brother Edmund Rice had to look out for more teachers to take charge of the new classes. Up to this time, men had joined his brotherhood as volunteers on their own initiative. He realized that he would now have to actively recruit many more men to keep up with the growth of his tuition-free school. He had his eyes out for men like himself, men who had done well in the business world (and therefore, would bring funds with them to help support his community and school). Edmund needed men who were motivated to reach out to the masses of disadvantaged people in the city.

According to Houlihan, as news of the success of Mount Sion was spread around Waterford, and as the school was expanding, in order to accommodate incoming students, Brother Edmund Rice had to look out for more teachers to take charge of the new classes. Up to this time, men had joined his brotherhood as volunteers on their own initiative. He realized that he would now have to actively recruit many more men to keep up with the growth of his tuition-free school. He had his eyes out for men like himself, men who had done well in the business world (and therefore, would bring funds with them to help support his community and school). Edmund needed men who were motivated to reach out to the masses of disadvantaged people in the city.